RSM Blog: The Science of Movement & Biomechanics

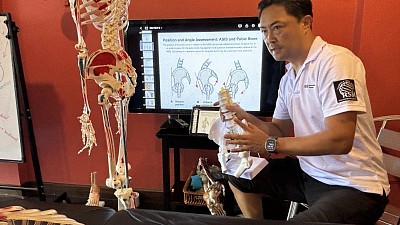

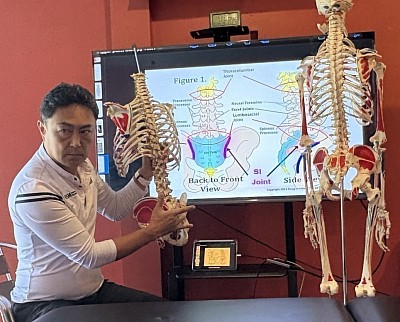

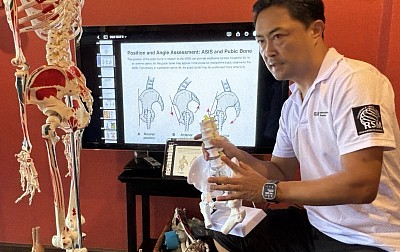

Integrated Deep Hip Rotator System and Femoral Head Centration

The piriformis, superior gemellus, obturator internus, and inferior gemellus function as a single integrated unit rather than as isolated muscles.They share a common insertional system and work together to control deep hip stability.

Among them, the obturator internus plays a specialized role. Its tendon-dominant, dense, and blade-like structure is designed primarily for tension regulation rather than force production.

The superior and inferior gemelli act as dynamic stabilizers, guiding and modulating the tension of the obturator internus tendon as it changes direction around the pelvis.

Through this coordinated system, the deep external rotators are responsible for precise femoral head centralization, ensuring optimal hip joint centration during movement and load transfer.

This mechanism explains why isolated activation of a single muscle is functionally unrealistic, and why dysfunction within this system should be understood as a unit-based coordination failure, not an individual muscle problem.

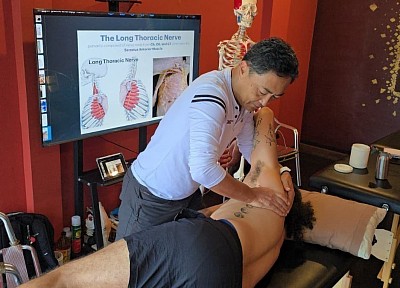

The Importance of Anatomy in Massage Education

I see a distinct dividing line between a standard practitioner and a true clinical specialist. It’s a line which is drawn by the depth of their understanding of the human frame. Many students arrive at our massage school in Thailand with a passion for healing, believing that intuition alone guides the hands. However, intuition without a map is merely guessing. When a therapist relies on memorized sequences rather than a concrete mental image of the structures beneath the skin, the treatment hits a ceiling. Conversely, a profound grasp of structure transforms a routine session into a targeted medical intervention.

Elevating Massage Therapy Through Science

The shift from relaxation to sports medicine-based massage therapy requires a fundamental change in mindset. We are not simply rubbing skin; we are manipulating a complex biological machine. When massage therapy is applied with scientific precision, it influences fluid dynamics, alters fascial tension, and resets neuromuscular tone. This level of efficacy is impossible without a rigorous study of the underlying architecture.

Consider a client presenting with chronic lower back pain. A superficial approach might suggest rubbing the erector spinae because that is where the symptoms manifest. However, a practitioner grounded in sports medicine recognizes that the lumbar spine is often a victim of hip immobility. The tightness in the lower back is a compensatory reaction to a restricted psoas major pulling on the lumbar vertebrae. Consequently, the massage therapy treatment plan shifts. We stop chasing the pain and start treating the dysfunction. This logical progression is the core value of our school and the foundation of effective massage.

Why Anatomy Knowledge Separates the Pros

Acquiring deep anatomy knowledge is not about memorizing Latin names; it is about visualizing depth and texture in three dimensions. When I teach palpation, I emphasize that every layer feels distinct. Muscle tissue has a specific grain and density. Connective tissue, such as fascia and tendons, feels more fibrous and unyielding. Nervous tissue is cord-like and highly sensitive.

Without precise anatomy knowledge, a therapist cannot differentiate between a trigger point and an inflamed bursa. Misidentifying these structures leads to improper technique application. Pressing hard on an inflamed bursa because it “feels tight” will only aggravate the inflammation. In contrast, knowing the exact location of the subacromial bursa allows the therapist to mobilize the surrounding muscles without compressing the sensitive fluid sac.

This distinction is critical for safety. The anterior neck contains the carotid artery and the vagus nerve. A therapist lacking human anatomy training might apply deep pressure here, inadvertently compressing the carotid sinus. Safety is the first priority. A massage applied without this awareness is not just ineffective; it is dangerous.

Decoding the Body for Better Results

The body functions as a tensegrity structure. A failure in one area ripples through the entire system. At RSM, we view the body not as a collection of isolated parts but as an integrated kinetic chain.

For instance, plantar fasciitis often presents as heel pain. However, investigating the body structurally often reveals that tight calf muscles are limiting ankle dorsiflexion, forcing the plantar fascia to overstretch. Going further up the chain, weak glutes may cause internal femoral rotation, collapsing the arch. By treating the calf and activating the glutes, we alleviate the tension downstream. Pain is rarely where the problem lives; it is merely where the system is failing to handle the load.

Integrating Physiology Knowledge

While anatomy provides the map, physiology knowledge explains the traffic flow. It is not enough to know where a muscle attaches; we must understand how the nervous system controls it. Massage is, in essence, a conversation with the nervous system.

We utilize concepts like Reciprocal Inhibition to manipulate muscle tone. If a client has a spastic hamstring, fighting it with deep pressure often triggers a protective stretch reflex. Instead, applying physiology knowledge, we know that contracting the opposing quadriceps forces the nervous system to relax the hamstring. This physiological hack achieves release without brutality.

Essential Anatomy in Practice

To illustrate the practical application of this philosophy, here are specific areas where anatomical precision dictates the success of the massage:

- The Suboccipital Triangle: Many tension headaches originate here. Precise palpation of the Rectus Capitis Posterior Minor, which bridges to the dura mater, can instantly relieve symptoms.

- The Psoas Major: Accessing this deep stabilizer requires intimate knowledge of the abdominal aorta and inguinal ligament to avoid injury.

- The Piriformis: Differentiating between piriformis syndrome and true lumbar radiculopathy requires specific provocation tests that rely entirely on anatomy.

- The Tarsal Tunnel: Medial ankle pain is often nerve compression, not a sprain. Knowledge of the flexor retinaculum allows the therapist to decompress the nerve rather than irritating it.

The Impact on Therapists

For therapists, essential anatomy is the ultimate safeguard against career-ending injuries. Many massage therapists burn out due to wrist pain caused by poor biomechanics. When therapists understand the leverage points of the skeleton, they learn to stack their joints and use their body weight rather than hand strength.

Targeting specific layers reduces the effort required. When you know exactly where the border of the scapula is, you can hook your fingers under the rhomboids with minimal force. You stop fighting the tissues and start working with natural planes.

In my experience, the moment a student truly grasps the connectivity of the muscular system is the moment they stop doing “routines” and start practicing therapy. That confidence is palpable. Therefore, for any aspiring therapist, the directive is clear: Go back to the texts. The power of your touch is directly proportional to the clarity of your anatomical understanding. Without it, you are merely skimming the surface. With it, you facilitate true recovery.

How Sports Massage Improves Performance: The Physiological Mechanisms

The Role of Sports Massage in Recovery

When we analyze how sports massage improves performance, we must first look at the mechanics of recovery. Intense physical exertion creates micro-trauma in the muscle fibers and generates metabolic waste. While the body naturally clears this waste, the process relies heavily on muscle contraction to pump venous blood and lymph back to the heart.

In RSM's Sports Massage Course, we teach that sports massage acts as a mechanical assist to this system. By manipulating soft tissue, we create external pressure gradients that force fluid out of interstitial spaces and into the vascular network. This accelerates the delivery of oxygen and nutrients required for repair. Consequently, the downtime between training sessions decreases. This allows athletes to maintain higher volumes of work without succumbing to fatigue.

Reducing Muscle Soreness and Inflammation

One of the most immediate barriers to high-level output is pain. Muscle soreness, particularly Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS), alters movement mechanics. When an athlete moves to avoid pain, they develop compensatory patterns that leak energy. It is vital to understand that this soreness is largely driven by inflammatory markers.

Research suggests that targeted therapy modulates this inflammatory response. By reducing inflammation, we prevent the “guarding” reflex where the nervous system tightens tissue to protect a painful area. At RSM, we use specific pressure to interrupt pain signals, a concept known as the Gate Control Theory. This lowers the perception of pain and allows for normal functional movement to return faster.

Optimizing Jump Performance Through Flexibility

Power is the product of force and velocity. In sports requiring explosive movement, restricted tissue is a major liability. We see this clearly when analyzing jump performance. The posterior chain must lengthen rapidly before contracting. If the hamstrings or calves are hypertonic, they limit the elastic energy storage required for a powerful jump.

Regular sports massage normalizes the length-tension relationship of these muscles. We mobilize the fascial layers to ensure they glide efficiently. When internal friction is reduced, the tendon can load effectively like a spring. This compliance allows the athlete to express their full power potential. By restoring ankle range of motion through deep calf work, we also allow for a deeper loading phase, which directly correlates to vertical height.

Essential Massage Techniques for Athletes

Clinical application requires a precise strategy. The massage techniques used must match the physiological goal of the athlete’s current cycle.

- Effleurage: Long, gliding strokes used to warm the tissue and assist lymphatic drainage.

- Petrissage: Kneading and lifting the muscle belly to separate fibers and break down adhesions.

- Friction: Concentrated pressure to remodel scar tissue in tendons.

Understanding when to apply these is key. For recovery, we use slower strokes to recruit the parasympathetic nervous system. Conversely, pre-event work utilizes rapid percussion to excite the nervous system. A massage therapist must be able to read the client’s autonomic state to deliver the correct stimulus.

Why Athletic Individuals Need Maintenance

There is a distinction between treating an injury and optimizing a system. Many athletic individuals wait until structural failure occurs before seeking help. This reactive approach is inefficient. Maintenance therapy serves as a diagnostic checkpoint.

By assessing tissue quality regularly, we can detect tightness in areas like the hip flexors or calves before they cause a tear. This proactive management prevents cumulative load from reaching the threshold of injury. For professional athletes, this consistency is often the difference between a long career and early retirement.

The Role of the Massage Therapist

The relationship between the massage therapist and the coach should be collaborative. We periodize treatments just as coaches periodize lifting. During high-volume build phases, we focus on systemic flushing and deep tissue pliability to manage fatigue. As competition approaches, we shift to mobilization. We avoid aggressive work that might lower muscle tone too much, as a certain amount of tension is required for reactivity.

Integration with Physical Therapy

Finally, it is crucial to integrate manual work with physical therapy. While PT focuses on corrective exercise, massage provides the mobility required to execute those exercises. If a hip capsule is too tight, a client cannot squat correctly. By releasing the restriction manually, we create a window of opportunity for strengthening.

This synergy is the key to improving performance. By prioritizing muscle recovery, neurological balance, and mechanical efficiency, we ensure that every ounce of effort in the gym translates to success on the field. This clinical precision is the standard we uphold at RSM.

How to Maintain Proper Body Mechanics

Understanding Body Mechanics and Kinetic Chains

New students often over-rely on raw muscle power to treat clients. They push with their shoulders and strain their lower backs. This approach inevitably fails. It leads to fatigue and can drastically shorten a therapist’s career. The solution is not strength; it is intelligence. Specifically, we must understand the physics of human movement.

Mechanics acts as the bridge between anatomy and longevity. When I speak of this concept, I refer to coordinating the skeletal, muscular, and nervous systems to maintain balance. If the skeletal structure is stacked correctly, gravity transfers the load through the bones rather than the soft tissue.

However, when alignment breaks, the load shifts. A misaligned joint creates a lever arm that amplifies force on surrounding muscles. Consequently, a small deviation in the hip results in tension elsewhere. This is the kinetic chain. In our massage workshops in Thailand, we teach that you cannot possess a healthy body without respecting these chains.

The Anatomy of Good Posture

Most people view posture as a static position. In reality, it is dynamic. It is the ability to maintain a neutral spine while moving. When the spine is neutral, the natural S-curve absorbs shock efficiently.

Loss of neutrality typically begins in the pelvis. If the pelvis tilts anteriorly, the lumbar spine arches excessively. Conversely, a posterior tilt flattens the lumbar curve, stressing the discs. Moving up the chain, the upper body compensates. We frequently observe the “forward head” position. This forces the trapezius muscles to overwork to support the skull.

To correct this, you must focus on body alignment. We use specific cues:

- Keep the head high, visualizing a string pulling the crown toward the ceiling.

- Retract the chin to align the ears over the shoulders.

- Ensure weight is distributed evenly across the feet.

This “stacking” minimizes muscular effort and allows the skeleton to do the work.

Safe Lifting and Injury Prevention

Whether adjusting a massage table or picking up groceries, the principles of physics remain constant. Improper lifting causes acute lower back issues. The error usually involves bending forward at the waist with straight legs.

When you bend at the waist, you create a long lever arm using your torso. The fulcrum is your lower back. Even a light object becomes heavy due to the torque generated. Avoid this position. The spinal erectors cannot safely lift loads from a stretched position.

Instead, change the mechanics of the movement:

- Approach the object closely to reduce the lever arm.

- Keep your back straight and neutral.

- Descend with your knees bent, pushing your hips back.

- Drive through the heels to stand.

By bending the knees, you utilize the gluteus maximus and quadriceps. Transferring the load to the hips protects the vulnerable spinal muscles. This adjustment is the cornerstone of injury prevention.

The Role of the Body in Massage Therapy

In our curriculum, adhering to proper body mechanics is mandatory. We view the therapist’s body as the primary tool. If the tool is broken, the treatment is ineffective.

When applying deep pressure, a therapist should not push with arm muscles. Pushing requires contraction, which wastes energy. Instead, we teach students to lean. They lock their joints into a safe position and lean their body weight into the client.

This technique utilizes gravity as a limitless source of energy. However, it requires balance. The therapist must maintain a wide stance. The spine remains straight, transmitting force from the legs, through the core, and out through the hands. If a student collapses their chest, the force gets trapped in the shoulder, leading to injury. We correct this by cultivating awareness. If the pressure comes from muscle tension, the mechanics are wrong.

Ergonomics and Proper Body Mechanics for Daily Life

Maintaining health requires vigilance outside the studio. Modern life forces us into sedentary patterns. Sitting in a chair for hours shortens the hip flexors, pulling the pelvis into an anterior tilt when we stand.

To break this cycle, apply care to your environment:

- Adjust monitors to eye level to prevent neck strain.

- Keep feet flat on the floor.

- Position keyboards to keep elbows at 90 degrees.

However, no chair is perfect. The best posture is a changing posture. We recommend moving every 30 minutes to rehydrate fascial tissues. Injury is rarely an accident; it is the result of long-term mechanical negligence.

Why We Prioritize Structural Logic

At RSM International Academy, our philosophy is grounded in science. Hironori Ikeda established this school to elevate standards through physiology, not mysticism. Understanding proper body usage is fundamental.

We analyze the vectors, levers, and loads acting on the system. Whether treating a patient or training a student, the goal is efficiency. By respecting the design of the human skeleton, we ensure longevity.

Implementing proper body mechanics is a discipline. You must catch yourself slouching and correct your form before lifting. Your body is the only vehicle you will ever own. Treat it with the respect a complex machine deserves. Maintain your alignment and move with intention. This is the path to sustainable health.

Essential Resources for Massage Therapy Students: Science & Skills

Foundational Medical Texts for Deep Anatomical Understanding

In my experience as a sports medicine instructor at our massage school here in Thailand, I often see students struggling to locate muscle insertions. This difficulty usually stems from a reliance on the two-dimensional diagrams found in standard massage school curriculums. When a therapist visualizes anatomy as a flat image, their palpation remains superficial. This lack of depth results in ineffective treatment.

To correct this, massage therapy students must invest in high-quality anatomical texts. A resource like Trail Guide to the Body is indispensable because it focuses on palpation paths, teaching you to navigate from a bony landmark to a muscle belly. Another critical text is Gray’s Anatomy for Students, which explains biomechanical relationships. Understanding that the biceps femoris shares an origin with the semitendinosus allows you to treat the entire posterior chain effectively.

I also recommend building a personal library containing reference books on pathology. Knowing the contraindications for conditions like deep vein thrombosis is the primary safety net for any serious practitioner.

Online Tools and Massage Apps for Visual Learners

While books provide intellectual depth, the human body is a dynamic machine. Static images cannot capture how muscle fibers slide during contraction. Consequently, I advise students to supplement their reading with online visualization tools.

Applications like Complete Anatomy allow you to strip away layers of fascia virtually. This digital dissection helps you understand depth, teaching you that treating the piriformis requires sinking through the gluteal mass. Online videos from reputable sources also serve a specific purpose. Watching a cadaver dissection reveals the reality of fascial adhesions ("fuzz"). Seeing the thickness of the thoracolumbar fascia compels you to adopt the deep tissue massage techniques we teach at RSM.

However, be cautious with random social media clips. Always verify what you watch against your anatomy texts.

Why Massage Therapy Journals Matter for Evidence-Based Practice

The field of massage therapy is shifting toward evidence-based medicine. Myths about "flushing lactic acid" are being replaced by physiological facts. To remain respected by other healthcare providers, you must engage with current research.

Accessing a research journal or database like PubMed is crucial. Reading systematic reviews on the efficacy of massage for chronic pain gives you confident talking points based on gate control theory rather than pseudoscience. This habit helps you understand the limitations of bodywork. Recognizing what massage cannot fix is just as important as knowing what it can, ensuring you make correct referrals when necessary.

Investing in Continuing Therapy Education and Mentorship

Graduating from a basic program is only the starting line. Real clinical competence comes from specialized therapy education. At RSM International Academy, we focus on Remedial Massage and Deep Tissue fundamentals because these modalities address the root causes of pain.

Advanced workshops refine your touch. Spending two days focusing solely on the shoulder complex allows you to develop the sensitivity to detect minor adhesions. Mentorship is equally vital. A senior practitioner who critiques your body mechanics can save you from career-ending injury.

When choosing advanced education, look for:

- Instructor Credentials: Teachers should have clinical backgrounds (e.g., Sports Medicine).

- Scientific Basis: Ensure the school curriculum is grounded in anatomy, not unverified theories.

- Hands-on Time: Skill acquisition requires guided practice.

Essential Resources for Career Longevity

Burnout is a high risk for massage therapists. To survive, you must view your body as your most valuable tool and invest in ergonomic resources.

A hydraulic table allows you to adjust height instantly, preserving your lumbar spine. Proper footwear is also non-negotiable; shoes with arch support prevent the plantar fasciitis that leads to compensation patterns in your own body. Finally, peer networks provide psychological support. Joining an association connects you with other massage therapists who understand the demands of the job.

Elevating Your Practice Through Curated Knowledge

The difference between a hobbyist and an expert lies in the resources they utilize. A hobbyist relies on intuition; an expert relies on data and anatomy. At RSM, I emphasize that massage is a cognitive process expressed through the hands. You must think before you touch. Utilize these tools to elevate your standard of care and deliver the specific, science-based benefits your clients deserve.

FAIR test at Approximately 60 Degrees of Hip Flexion as the Most Revealing Diagnostic Position

For many years I have evaluated clients whose hip or buttock pain sharply increases during the FAIR position. FAIR refers to flexion, adduction and internal rotation of the hip, and the position becomes most diagnostically accurate when the hip is flexed to approximately sixty degrees. At this angle the deep-gluteal interval tightens in a very specific way. The piriformis begins to shift its rotational function, the obturator complex becomes tensioned, and the sciatic corridor narrows just enough to expose underlying dysfunction that is often invisible in neutral hip positions. This sixty-degree window is where countless clients—athletes, office workers, older adults, people recovering from injuries and individuals who simply sit too long—show their clearest symptoms.

Across decades of hands-on work, one observation has repeated itself with remarkable consistency. People who develop lateral-hip or trochanteric pain often walk with a pronounced lateral pelvic shift. It is especially common in heavier individuals and in many women who demonstrate a side-to-side pelvic drop with each step. The mechanism is simple when you see it enough times. Excess pelvic shift increases compression over the gluteus medius and minimus tendons and the trochanteric bursa. FAIR—because it exaggerates adduction and internal rotation—magnifies the same forces that irritate these tissues during walking. For these clients the FAIR test is not a piriformis problem at all. It is a reflection of chronic lateral-hip overload that has been silently developing through years of compensatory gait.

Deep buttock pain during FAIR often reveals irritation within the sciatic corridor rather than an isolated piriformis syndrome. Many clients spend decades sitting with a habitual pelvic rotation, a leg crossed over the other or a consistently flexed lumbar posture. These patterns bind the deep gluteal fascia, limit capsular movement and create a narrow channel in which the sciatic nerve becomes vulnerable. FAIR does not create this vulnerability. It merely exposes it. I have seen this pattern in athletes and in people who have never trained a day in their lives.

There is also a group whose FAIR-induced pain appears not in the buttock but in the medial thigh. This clinical picture is almost always tied to the obturator nerve or to tension within the fascial envelope of the adductor complex. Hip adduction and internal rotation load this region more than most people realize. Many clients who sit long hours, who have old groin strains or who lack genuine hip-rotation capacity experience a distinct medial-thigh pain during FAIR. In these cases the problem is neither piriformis nor sciatic. It is a diagnostic doorway into a deeper issue of obturator-related irritation that is frequently misclassified in standard practice.

Another consistent pattern emerges in clients with lateral hip pain and tenderness around the greater trochanter. These individuals may sleep predominantly on one side, collapse their hip during walking, or rely on compensatory tension in the iliotibial band to stabilize a weak pelvic structure. When placed in FAIR, the lateral hip becomes compressed under conditions identical to those experienced during daily walking. What appears to be a positive piriformis test is, in reality, a clear sign of greater-trochanteric overload and gluteal-tendon sensitization.

I have encountered a different subset of clients in whom FAIR provokes deep posterior-hip discomfort without sciatic characteristics. This arises when the deep external rotators—obturator internus, obturator externus, the gemelli, or quadratus femoris—lose their stabilizing function. These muscles quietly hold the femoral head inside the acetabulum during ordinary tasks such as climbing stairs, rising from a chair or simply turning in bed. When they fail, the FAIR position reveals their weakness instantly. The discomfort is unmistakable for anyone who has palpated these structures as often as I have.

Finally、there are individuals who feel a sharp or aching sensation near the ischial tuberosity during FAIR testing. This region hosts not only the proximal hamstring origin but also the pathways of the sciatic nerve and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve. People who sit on firm surfaces for long periods, long-distance drivers, and those with old hamstring injuries often fall into this category. The FAIR position tensions the posterior-thigh structures far more than it loads the piriformis, and recognizing this distinction is essential for accurate diagnosis.

After years of observing thousands of bodies, the conclusion is clear. FAIR-related hip pain is not a single condition. It is a cluster of different anatomical patterns expressed through one provocative position. Deep buttock pain aligns with the sciatic corridor. Medial-thigh discomfort reveals obturator or adductor fascial involvement. Lateral-hip pain exposes gluteal-tendon compression and trochanteric overload. Posterior-hip tightness arises from deep-rotator dysfunction. Pain near the ischial tuberosity reflects irritation of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve or proximal-hamstring tissues. Each pattern has a unique mechanical origin and demands a specific therapeutic strategy.

At RSM International Academy, these distinctions are not theoretical. They are the foundation of how we teach manual therapy, movement interpretation and corrective intervention. Students learn to read the FAIR position not as a simple piriformis test but as a diagnostic system that reveals the deeper organization— or disorganization—of the hip. Whether through Sports Massage, Trigger Point Therapy, Deep Tissue Massage, Remedial Massage or Dynamic Myofascial Release, the goal is always the same. Understand the pattern. Touch the truth beneath the surface. Intervene with precision, not assumption.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc sports medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

References

1) Benson E et al. Deep gluteal syndrome and posterior hip pain. Clinical Orthopaedics

2) Bradshaw C and McCrory P. Obturator nerve neuropathy and groin pain patterns. Sports Medicine.

Tennis Elbow and Golfer’s Elbow as Failures of Wrist Centrifugal Adaptation and Shoulder Kinetic Chain Function

Lateral and medial epicondylitis have traditionally been described as local overuse injuries involving the wrist extensors and flexors. From a modern sports medicine and biomechanical perspective however these conditions are better understood as the result of two interacting problems. The first is the inability of the wrist to adapt to rapidly increasing centrifugal force at impact. The second is a breakdown of the kinetic chain at the glenohumeral joint which forces the forearm to compensate through excessive pronation and supination.

During a tennis stroke a golf swing or any striking motion the racket club or bat generates a marked increase in centrifugal force from impact into the follow through. A healthy wrist responds to this force by allowing a brief delayed motion that creates functional spacing between the carpal bones and the radius and ulna within the wrist joint. This spacing allows traction forces to be dissipated across the entire wrist complex rather than transmitted directly into the elbow. The carpus and distal forearm effectively work as a shock absorber that protects the epicondylar tendon origins from excessive eccentric overload.

When an athlete stiffens the wrist with excessive muscular co contraction this protective spacing is lost. The wrist can no longer absorb the centrifugal pull of the racket or club and the resulting force is transferred almost directly to the forearm muscles. The wrist extensors and flexors are then subjected to rapid eccentric loading at the moment of impact. Over time this leads to microtrauma and degenerative change at the lateral or medial epicondyle which is the classic presentation of tennis elbow and golfer’s elbow. Biomechanical studies have repeatedly shown that rapid eccentric overload of the wrist extensors during impact is a key mechanism in the development of lateral epicondylitis.

The picture becomes more complex when we consider the glenohumeral joint. In efficient overhead and striking mechanics the shoulder provides a substantial portion of the rotational motion required for stroke production through well coordinated internal and external rotation. When glenohumeral internal rotation is limited a condition often referred to as GIRD the athlete may attempt to square the racket face or clubface by increasing forearm pronation. Conversely when external rotation is insufficient the athlete may rely excessively on supination. In both cases shoulder rotation that should occur at the GH joint is shifted distally into the forearm and elbow.

This compensatory strategy disrupts the kinetic chain. Instead of the shoulder trunk and lower body sharing the load the elbow is forced to manage both the rotational demands of the stroke and the high eccentric forces generated at impact. The elbow becomes a bottleneck in the energy flow. Several kinetic chain studies have shown that altered shoulder mechanics and deficits in total rotational motion are associated with an increased risk of elbow injury in throwing and racket sport athletes.

In this framework tennis elbow and golfer’s elbow are not simply local tendon pathologies. They are manifestations of a global mechanical problem in which the wrist fails to create adequate space and shock absorption under centrifugal load and the shoulder fails to contribute its share of rotational motion. The forearm responds with excessive pronation or supination and the epicondylar structures are exposed to repeated eccentric stress.

Effective prevention and rehabilitation therefore require more than localized treatment of the elbow. They must address the ability of the wrist to move freely and absorb force and they must restore glenohumeral internal and external rotation so that the kinetic chain from shoulder to wrist can function as a coordinated system. Athletes who develop a supple wrist and an efficient shoulder driven kinetic chain can dissipate impact forces far more effectively and significantly reduce the mechanical burden placed on the elbow.

At RSM International Academy these biomechanical principles form the foundation of our advanced professional training curriculum. Our Sports Massage and Remedial Massage programs provide an in depth understanding of kinetic chain mechanics for overhead athletes including glenohumeral internal and external rotation forearm pronation and supination and the wrist’s shock absorption mechanism under centrifugal load.

In our Dynamic Myofascial Release course students study fascial dynamics joint capsule mobilization and upper extremity kinetic chain integration with exceptional depth and precision. These skills represent essential competencies for elite sports trainers and performance clinicians. The curriculum is specifically designed to prepare practitioners to evaluate and correct dysfunctional movement patterns in athletes at every level ensuring they gain the advanced skill set required in modern sports medicine.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc sports medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

Reference

1) De Smedt T et al. Lateral epicondylitis in tennis: update on aetiology diagnosis and treatment. British Journal of Sports Medicine.

2) Riek S et al. A simulation of muscle force and internal kinematics of the forearm during backhand stroke in tennis. Journal of Biomechanics.

Sports Medicine Approach to Upper-Extremity Pain and Kinetic-Chain Dysfunction

Upper-extremity disorders such as Pronator Teres Syndrome, Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, and De Quervain’s tenosynovitis cannot be understood in isolation. In sports medicine, these conditions emerge from failures across the kinetic chain: shoulder rotation, forearm pronation mechanics, wrist deviation control, tendon glide, neural tension, and joint centralization. When even one link in this chain loses mobility or alignment, the athlete compensates, and the overload expresses itself where the system is weakest.

In advanced assessment, we look first at the essential movement triad: glenohumeral internal rotation, forearm pronation, and wrist flexion–ulnar deviation coupling. These motions must work together in a synchronized pattern for throwing, tennis strokes, golf swings, and high-velocity upper-limb actions. When GH internal rotation is restricted, the athlete is forced to overuse the forearm, especially the pronator teres. When wrist mobility—particularly flexion and ulnar deviation—is limited, the body generates power through compensatory forearm pronation rather than through the shoulder–trunk system. Over time, this creates fibrosis, altered tendon glide, neural tension, and joint malalignment that eventually present as pain.

Joint centralization plays a critical role in performance and injury prevention. When the glenohumeral joint, elbow joint, radiocarpal joint, or thumb CMC joint falls outside its ideal position, the surrounding tissues must absorb abnormal load. Without centralization, the kinetic chain cannot transfer energy efficiently, and the body responds with compensatory recruitment patterns. These are the patterns we routinely identify at RSM International Academy during our Sports Medicine Massage and Trigger Point Therapy training.

In de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, loss of glide in the first dorsal compartment prevents the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) from moving smoothly beneath the extensor retinaculum. The tendon sheath thickens, the retinaculum becomes less compliant, and the thumb CMC joint often shifts slightly from its centered position. This misalignment increases friction, amplifies mechanical stress, and produces the classic radial-sided wrist pain commonly seen in massage therapists, caregivers, and female practitioners in their forties and fifties. In many of these cases, the problem is not inflammation—it is a failure of myofascial glide, tendon glide, and joint centralization.

In my clinical experience, a targeted five-to-eight-minute intervention—restoring retinacular mobility, improving sheath elasticity, releasing APL/EPB adhesions with cross-fiber techniques, and applying precise high-velocity low-amplitude mobilization to the thumb CMC joint when indicated—can dramatically reduce pain. This rapid response demonstrates the mechanical nature of the dysfunction and the importance of restoring glide and centralization.

Pronator Teres Syndrome follows a similar logic. When GH internal rotation is limited or the athlete over-relies on forearm pronation to generate power, the pronator teres becomes chronically overloaded. Fibrosis forms between its two heads, and the median nerve loses its ability to glide. Neural tension increases, forearm mechanics collapse, and wrist-control muscles overwork to compensate. At RSM International Academy, therapists learn the Pronator Teres Provocative Test, which uses resisted pronation with varying elbow flexion to identify nerve compression at the pronator. This differentiates it from distal compression inside the carpal tunnel, allowing precise treatment rather than generalized forearm work.

Accurate assessment is central to RSM’s methodology. The Finkelstein test remains the most reliable provocation method for de Quervain’s, while the Pronator Teres Provocative Test isolates proximal median nerve compression. But evaluation never stops at the pain site. Students are trained to examine GH internal rotation, scapular rhythm, neural glide throughout the brachial plexus, wrist flexion–ulnar deviation coupling, and thumb CMC joint alignment. Only by connecting these elements can a therapist identify true causation rather than chasing superficial symptoms.

Treatment at RSM International Academy integrates Trigger Point Therapy, Sports Medicine Massage, joint mobilization (HVLA/LVLA), myofascial release, and neural mobilization into a single unified system. Trigger points in the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, brachioradialis, and intrinsic thumb muscles are released not as isolated techniques but in coordination with joint corrections and nerve-glide restoration. Our approach views pain as the final output of a dysfunctional kinetic chain, not the primary target.

Athletes who fail to maintain centralization and aligned movement patterns eventually overload the wrist and thumb structures. When the wrist lacks mobility—especially flexion or ulnar deviation—the body compensates with excessive pronation during strokes or swings. This compensation loads the pronator teres, tightens the APL and EPB, increases retinacular stress, and ultimately produces nerve and tendon pathology. Correcting these movement faults restores efficient load distribution and allows athletes to perform with power, speed, and longevity.

RSM’s training is fundamentally about teaching therapists to see this big picture. By combining sports medicine principles with hands-on manual therapy, our programs prepare practitioners to identify the true source of dysfunction, restore alignment and glide across all tissues, and deliver results that matter in real-world human movement.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. Persistent numbness, weakness, or night pain should be evaluated by a medical professional.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc sports medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

Eeference

1) Goel R, Abzug JM. De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis: A Review of the Rehabilitative Options. Hand (N Y). 2015 Mar;10(1):1–6. doi:10.1007/s11552-014-9652-7.

2) Sharma K, Dididze M, Ganesh A. Pronator Teres Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526090/

Safe Manual Therapy Strategies for Lumbar Spondylolisthesis and Extension-Related Symptoms

Lumbar spondylolisthesis is one of the conditions where symptoms often intensify during extension. Athletes and trainers who spent their younger years lifting heavy weights, teaching weight training, or loading the lumbar spine repeatedly frequently present with this pattern. Many of them felt “strong” in their twenties and thirties, yet early signs of instability were already present. When these individuals reach their mid-fifties and begin to gain weight, the unstable motion segment becomes symptomatic and the condition progresses into a clear spondylolisthesis. I have seen this repeatedly in the last three to four years, particularly among former weightlifting instructors who can no longer perform or teach lifts and now depend on developing manual therapy skills to maintain their careers.

In extension-sensitive spondylolisthesis, the forward slip of the vertebral body increases shear forces at the affected level, most commonly L4–L5 or L5–S1. Even a slight increase in lordosis can provoke burning, radiating discomfort, a sense of pressure across the lumbosacral junction, or irritation that spreads into the gluteal region or the leg. These patients often arrive already guarded, and even minor movements toward extension reproduce their pain.

For this group, positioning is the first treatment. A pillow placed under the chest increases lordosis and almost always worsens symptoms. A pillow placed under the abdomen does the opposite. It draws the lumbar spine toward a neutral or slightly flexed alignment and reduces anterior shear at the slipped segment. When both knees are gently brought toward the chest and traction is applied slowly, many patients experience immediate relief, not because of force but because the canal opens just enough to calm the irritated nerve root.

Manual therapy must respect the mechanical instability. Deep tissue pressure directly over the lumbar facets or into the multifidus is rarely beneficial at this stage and may trigger further muscle guarding. Selective work is more effective. Trigger point techniques can be applied safely to symptomatic myofascial regions around the lumbar spine, gluteal complex, and lateral hip without loading the unstable level itself. Controlled manual contact reduces peripheral tension while protecting the deeper stabilizers that the patient still depends upon.

Understanding the segmental level matters. In the clinical example, the narrowing and the forward slip are most consistent with L4–L5, although individual anatomy may differ. Regardless of the exact level, the principle remains constant. Flexion bias reduces symptoms, while extension increases neural irritation and should be avoided in early stages.

What has become increasingly clear in my own clinical work is how often former trainers follow this pattern. Many of them lifted heavy loads for decades, then slowed down, gained weight, and now find themselves unable to demonstrate or teach weightlifting technique. They turn toward massage therapy and clinical bodywork because it becomes their livelihood. These therapists must not only protect their own spine but must also recognize the same risk factors in their clients. Spondylolisthesis is not rare among former strength athletes, and understanding safe manual strategies is part of professional survival.

A careful combination of flexion-biased positioning, symptom-controlled manual therapy, and precise palpation offers a practical and safe method for managing this condition. When symptoms become stable, gradual strengthening and controlled movement retraining can begin. The priority in early care is always protection of the unstable segment and avoidance of strategies that increase extension stress.

This is not theory. It is a pattern I have observed repeatedly across many years of working in sports medicine. The athletes and trainers who developed spinal instability early in life and gained weight later often present with the most predictable extension-aggravated symptoms. Their clinical presentation, response to manual therapy, and recovery pattern follow the same logic. My goal is to offer a framework that therapists with one or two years of experience can apply safely, while still reflecting what senior clinicians encounter in practice.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

References

1) Kalichman, L., & Hunter, D. (2008). Lumbar spondylolisthesis: A systematic review of the literature. Spine Journal.

2) Murtagh, R. (2008). Diagnosis and conservative management of spondylolisthesis. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation.

Pelvic Rotation Patterns and Their Impact on the Piriformis and Sciatic Nerve in Right-Dominant Athletes

Athletes who rely heavily on their right side, such as right-handed golfers, tennis players, and rotational-sport practitioners, often develop a predictable pattern of muscular tension around the pelvis and posterior hip. These adaptations are not random; they arise from repeated movement strategies that place asymmetrical forces on the deep hip rotators, the piriformis muscle, and the neural structures that pass beneath or through it. In many right-dominant athletes, the pelvis tends to rotate toward the left during the swing or stroke phase, creating increased demand on the right posterior chain while the left side becomes the anchor for stability and directional control.

From a muscular perspective, the right piriformis and the lateral portion of the right hamstring frequently become overactive because they must decelerate the rapid left-rotational motion of the pelvis. Over time, this load may produce stiffness or localized tenderness in the deep gluteal region. On the opposite side, the left hip commonly demonstrates increased tension in the tensor fasciae latae, the gluteus medius and minimus, the adductor group, and the medial hamstrings. These muscles function as stabilizers during rotation and often accumulate tension as they control the rotational axis of the pelvis.

This pattern is clinically relevant because approximately ten to seventeen percent of the general population exhibits anatomical variations in the relationship between the piriformis and the sciatic nerve. In some individuals, part of the sciatic nerve may pass above, below, or even through the piriformis. When this variation is combined with rotational sports, the likelihood of compression or irritation increases, especially as athletes reach their mid-thirties and forties. Reduced muscle elasticity, mild fibrosis in the deep hip rotators, and decreased neural glide contribute to symptoms such as buttock pain, posterior thigh discomfort, or sensitivity along the ischial region.

Assessment should begin with a structured sequence. The FAIR position—hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation—remains one of the most practical ways to engage the piriformis and observe irritation patterns. Maintaining the hip near sixty degrees of elevation is essential, as this angle maximally loads the deep external rotators. The location of the athlete’s pain provides useful diagnostic clues. Deep pain near the ischium or the lateral hamstring region may suggest involvement of the inferior cluneal nerve. Medial hamstring discomfort or symptoms closer to the inner thigh more commonly point to tension in the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve. If the athlete reports isolated deep-gluteal pressure, a pure piriformis tightness pattern is likely.

A second stage involves assessing neural mobility. Extending the knee from the testing position increases tension along the tibial nerve and the deep fibular nerve. Restrictions here may recreate symptoms along the calf or even near the peroneus longus, indicating reduced neural glide rather than a muscular source of pain. The Straight Leg Raise and its variations help determine whether the problem originates from the nerve or from the surrounding soft tissue.

If symptoms improve with myofascial release, trigger point therapy, or neural-glide techniques, the primary issue is usually functional. However, persistent symptoms despite appropriate manual therapy may indicate an underlying structural factor, such as an anatomical variation of the sciatic nerve or true deep-gluteal entrapment. In those cases, referral to a physician is appropriate. Ultrasound-guided injections—performed with imaging rather than a blind approach—are now the clinical standard when conservative care is insufficient. They offer both diagnostic clarity and therapeutic value without the risks associated with unguided injections into the deep hip.

This integrative approach, combining movement analysis, soft-tissue assessment, and neural evaluation, provides a reliable framework for understanding and treating posterior hip pain in right-dominant rotational athletes. It respects both the complexity of pelvic mechanics and the individual variations that influence symptoms, allowing clinicians and practitioners to guide athletes toward safer and more efficient movement patterns.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

References

1 ) Beaton, L. E., & Anson, B. J. (1937). The relation of the sciatic nerve and its subdivisions to the piriformis muscle. Anatomical Records.

2)Windisch, G., Braun, E. M., Anderhuber, F., & Ulz, H. (2007). Anatomical variations of the piriformis muscle and the sciatic nerve. Clinical Anatomy.

Understanding Ankle Dorsiflexion Limitation and Its Impact on Lumbar and Hip Compensation in Sports Movement

In many athletes and general clients I’ve worked with over the years, one of the most consistent patterns I observe is how a simple restriction in ankle dorsiflexion can quietly influence the entire kinetic chain. It rarely stays at the ankle. The moment dorsiflexion becomes limited—whether from muscular tightness, joint restriction, or deep fascial tension—the body tries to find a way around it. And the compensation almost always travels upward into the knee, the hip, and eventually the lumbar spine. Once you see this pattern enough times in real people, it becomes impossible to ignore.

When the ankle cannot dorsiflex properly, the knee loses its ability to translate forward in a natural way. This forces the hip to take on more flexion than intended, and in many athletic positions—especially the so-called “power position”—the lumbar spine begins to extend excessively to maintain balance. This is one of the hidden pathways by which dorsiflexion limitation contributes to low back discomfort. It’s not a dramatic shift; it’s subtle. But repetition during walking, training, lifting, or sport compounds the stress. The more limited the ankle is, the more the lumbar spine and hip must compensate.

One of the primary reasons dorsiflexion becomes restricted lies in the posterior compartment of the lower leg—particularly the gastrocnemius and soleus. Shortening, chronic tightness, or active trigger points in these muscles reduce the available tibial translation over the talus. But the deeper contributors are just as important: the tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, and flexor digitorum longus often create a kind of “deep compartment stiffness” that many clinicians overlook. These deeper muscles don’t scream for attention, but they significantly alter ankle mobility when they tighten.

Just as critical is the movement of the talus itself. Proper dorsiflexion depends on adequate posterior glide of the talus. When this glide becomes restricted—whether due to joint capsule stiffness, retinaculum tension, local swelling, or even decreased sliding of the fat pad—the ankle simply cannot express its full range. Without this posterior movement, the tibia is forced to compensate, and the chain reaction quickly spreads upward. In my experience, once talar mobility is restored, many seemingly unrelated movement problems begin to improve almost immediately.

Athletes often feel this during squatting, lunging, or deceleration drills. With limited dorsiflexion, they shift their weight backward, externally rotate at the hip to “open space,” or overextend the lumbar spine to stay upright. These are not conscious choices; they are automatic compensation strategies the body uses to keep the movement going. But these same patterns, repeated daily, become a source of stress for the lumbopelvic system.

Addressing dorsiflexion limitation effectively requires working both the muscular system and the joint mechanics. Soft-tissue work for the gastrocnemius, soleus, and deep posterior compartment is essential, but equally important is mobilizing the talus, improving retinaculum elasticity, and restoring the natural glide of the joint complex. When the ankle regains its functional alignment and mobility, the hip and lumbar spine immediately reduce their compensatory load.

In sports medicine, these details matter. Small limitations in foundational joints—like the ankle—shape movement quality more than people realize. When dorsiflexion is restored, the power position becomes cleaner, knee alignment improves, the hip works through its intended range, and lumbar extension stress decreases. In short: by improving the mobility of one small joint, the entire system moves closer to its natural design.

This biomechanical chain is something I’ve seen over and over again in real cases. Once you learn to recognize it, the relationship between ankle mobility and lumbar comfort becomes unmistakable.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

References

1) Hoch, M. C., & McKeon, P. O. (2011). The Effect of Ankle Joint Mobilization on Dorsiflexion Range of Motion and Dynamic Postural Control. Journal of Athletic Training, 46(1), 22–29.

2) Macrum, E. et al. (2012). Ankle Dorsiflexion Range of Motion Influences Dynamic Knee Valgus in Athletic Movement. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 21(1), 1–6.

Synchronizing Body Axes and Center of Gravity through Balance Ball Training

The essence of Sports Medicine-Based Performance Training lies in mastering the synchronization between the body’s gravitational center (COG) and the central axis of unstable surfaces, such as balance or BOSU balls. This process defines true postural alignment: by aligning the kinetic chain with the ball’s fluctuating center, practitioners establish stability through motion, not stillness. It is a process of neuromuscular calibration, where each muscle group learns its precise contribution to whole-body equilibrium.

Within the Dynamic Postural Assessment framework of RSM International Academy, this synchronization process re-educates the kinetic chain through movement transitions—from static to dynamic and dynamic to static. By refining proprioceptive sensitivity and fascial tension distribution, practitioners cultivate a conscious awareness of their Body Axis Alignment. This enhances control in sport-specific actions, reduces compensatory patterns, and improves motor efficiency.

In clinical and athletic settings alike, this synchronization is essential not only for postural correction but also for pain management and rehabilitation. Once the kinetic chain becomes functionally integrated, the athlete achieves both mechanical efficiency and movement fluidity—hallmarks of high-level sports medicine practice.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

References:

1) Willardson, J.M. (2007). Core stability training: applications to sports conditioning programs. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(3), 979–985.

2) Panjabi, M.M. (1992). The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I: Function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. Journal of Spinal Disorders, 5(4), 383–389.

Kinetic Chain Training on Unstable Surfaces for Dynamic Postural Assessment

In Sports Medicine-Based Performance Training, the development of neuromuscular integration through unstable surfaces—such as BOSU and balance balls—is fundamental. These tools challenge both the ascending and descending kinetic chains, forcing the body to maintain alignment through constant micro-adjustments. Each subtle movement activates proprioceptors and enhances intermuscular coordination, promoting a dynamic equilibrium between the body’s Center of Gravity (COG) and the base of support.

At RSM International Academy, this method is not used for simple balance exercises but as an advanced clinical approach to Dynamic Postural Assessment. Through controlled instability, practitioners evaluate how kinetic chain dysfunctions and pain-avoidance postures (PAP) manifest under load and motion. By analyzing compensatory mechanisms and re-educating proprioceptive pathways, students learn to correct postural inefficiencies and restore functional movement.

This form of neuromechanical conditioning creates adaptability across joints and fascia, stabilizing body axes through both ascending and descending kinetic synchronization. Ultimately, the athlete or therapist gains refined control of postural reflexes—vital for pain reduction, joint mobility, and long-term athletic performance.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Neurodynamics & Sports Biomechanics Specialist

References:

1) Behm, D.G., & Colado, J.C. (2012). The effectiveness of resistance training using unstable surfaces and devices for rehabilitation. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(3), 716–726.

2) Zazulak, B.T., Hewett, T.E., Reeves, N.P., Goldberg, B., & Cholewicki, J. (2007). Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(7), 1123–1130.