RSM Blog: Manual Therapy Techniques

Mastering Effective Stretching Techniques in Massage

Beyond Passive Stretching in Massage

Many therapists believe that simply pulling a limb creates flexibility. However, without engagement, stretching often triggers a protective reflex in the muscle spindles. This reaction causes the muscles to contract rather than relax, often exacerbating pain instead of relieving it. In RSM's Massage Workshops in Thailand, I emphasize that massage is not just mechanical manipulation; it is a neurological dialogue.

To be effective, we must respect the nervous system. Stretching techniques applied clinically must target the Golgi Tendon Organs to lower resting tone. If a therapist ignores these mechanisms, they are merely tugging on resistant structures. Therefore, the goal of any stretch within therapy is to obtain neurological permission for the tissue to lengthen.

Myofascial Release and Fascial Stretch

Force transmission occurs through the fascial network, not just independent muscle pulleys. When fascia is densified, a standard static stretch compresses the joint rather than elongating the tissue. For example, if the lateral thigh fascia is adhered, stretching the quad simply jams the knee.

To correct this, we utilize myofascial release before elongation. This prepares the tissue by creating a shearing force that restores sliding surfaces. This concept of fascial stretch focuses on the interface between compartments. We also prioritize pliability stretching, ensuring the tissue is hydrated and compliant. A shorter, pliable muscle is infinitely more functional than a long, stiff one. Combining stretch massage strokes with elongation encourages this hydration, offering superior results to dry stretching.

Implementing Resistance Stretching and Techniques

One of the most potent tools for correcting dysfunction is resistance stretching. By engaging the muscle eccentrically while it lengthens, we reorganize collagen and break down scar tissue. This active approach generates heat and re-educates the nervous system more effectively than passive methods.

We often integrate PNF stretching (Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation) to utilize post-isometric relaxation. Contracting a tight muscle against resistance loads the tendon, triggering an inhibition reflex that allows for a deeper range of motion. For athletes, dynamic stretching is also employed to maintain temperature and stimulate mechanoreceptors.

When integrating these methods, we follow a specific protocol to ensure the client retains the benefits:

- Preparation: Use massage to warm the tissue.

- Action: Apply assisted stretching techniques or PNF.

- Re-education: Have the client perform active movement to “save” the new range.

Advanced Isolated Stretching

Precision differentiates a general rub from clinical therapy. Isolated stretching targets specific muscle bellies rather than general chains. For instance, stretching the Psoas requires locking the lumbar spine to prevent compensation. If we fail to isolate, the force dissipates into hypermobile joints, potentially causing injury.

Assisted stretching techniques allow the therapist to control these vectors precisely. By stabilizing the pelvis, we can address a specific muscle like the Quadratus Lumborum without compromising the spine. This level of detail defines the curriculum at RSM. We do not view stretch therapy as separate from soft tissue work. They are symbiotic.

By combining flexibility protocols with anatomical precision, we do more than provide temporary relief; we improve long-term mobility. Therapists who master these techniques can solve complex pain patterns that standard treatments miss. Whether utilizing stretching assisted by pressure or active resistance, the focus remains on functional restoration.

Shiatsu Massage for Lower Back Pain

The Physiological Impact of Shiatsu

At RSM, we approach bodywork through the lens of sports medicine. While traditional modalities often focus on relaxation, the clinical application taught in our Shiatsu Massage Course requires a deeper understanding of physiology. Treating lower back pain requires more than generic contact. It requires precise manipulation of the nervous system and fascial layers.

When we apply perpendicular compression, we are not simply mashing muscle tissue. We are engaging the mechanoreceptors within the fascia to downregulate muscle tonus. This stimulation shifts the client from a sympathetic “fight or flight” state into a restorative state. For a person suffering from acute lower back tightness, this neurological reset is the prerequisite for structural change. Without addressing this neurological component, any massage is simply fighting against a guarded nervous system.

We often observe that local ischemia, or lack of blood flow, is a primary driver of discomfort in the low back. Static muscle contraction compresses capillary beds and prevents the evacuation of metabolic waste. The vertical force applied during shiatsu massage creates a temporary ischemic compression. This is followed by a rush of fresh, oxygenated blood upon release. This “pump mechanism” restores cellular health and pliability to the paraspinal muscles.

Decoding the Mechanism of Pain

To effectively treat the lumbar spine, a practitioner must look beyond the site of discomfort. The lumbar vertebrae are effectively the victims of a war being fought between the thoracic spine and the pelvis. We teach students to identify the causal chain rather than chasing symptoms of back pain.

A common pattern involves the Quadratus Lumborum (QL). When the QL becomes hypertonic, it pulls the pelvis into an anterior tilt or hikes the hip. This asymmetry forces the lumbar facets to jam together. This creates sharp, localized pain. However, the chain often extends further down.

Tight hamstrings are another frequent culprit. When the hamstring group is shortened, it pulls the ischial tuberosity downward. This creates a posterior pelvic tilt and flattens the natural lordotic curve of the lower back. A flat back loses its shock-absorbing capacity. This leads to bulging discs and nerve root compression. Therefore, massage therapy targeting the hamstrings is often more critical than rubbing the back itself. The lower back pain is merely the symptom of these biomechanical imbalances.

Precision Massage Protocols for the Back

In our courses, we emphasize that techniques must follow anatomy. The application of manual force aligns with specific anatomical landmarks. The Bladder Meridian, for instance, runs parallel to the spine and overlaps the Erector Spinae muscle group.

When treating the Erector Spinae, the therapist must locate the groove between the spinous processes and the muscle belly. Applying thumb compression here addresses the multifidus muscles. If these deep stabilizers are atrophied, the larger global movers overwork to compensate. This leads to fatigue and strain.

We utilize a specific sequence to address these layers. We begin at the sacrum to release the fascia, providing immediate slack to the spinal column. We then address the Ilio-Lumbar Ligament, a frequent site of chronic lower back inflammation. Finally, we target the Gluteus Medius and Minimus. Trigger points in these muscles refer sensations directly into the lumbar region. This methodical approach distinguishes professional shiatsu therapy from casual bodywork.

Evidence Supporting Massage Therapy

The medical community increasingly recognizes the value of manual manipulation. A study often validates what manual therapists have observed for centuries. Touch modulates pain perception via the Gate Control Theory. The non-painful input of touch inhibits the transmission of pain signals to the brain.

Research frequently compares a shiatsu group receiving targeted therapy against a control group. Results often indicate that the massage group experiences reduced cortisol and increased serotonin. Breaking the cycle of chronic discomfort requires a dual approach. We need mechanical release of soft tissue and chemical regulation of the brain’s pain matrix. At RSM, we integrate these findings into our curriculum to ensure our graduates practice evidence-based care.

RSM’s Clinical Approach to Massage

The distinction between a relaxation session and a clinical massage lies in assessment. Before a student at RSM lays a hand on a client, they must perform a visual and palpable assessment. We observe the client’s gait, their standing posture, and the rotation of their hips.

Our curriculum relies on the “thumb compression” technique. It allows for a level of diagnostic sensitivity that tools cannot replicate. Through the thumb, a therapist can detect changes in tissue temperature and texture. This sensory feedback guides the massage therapy in real-time. This dialogue between the practitioner and the client’s body is the essence of effective therapy.

Integrating Therapy and Movement

Recovery is rarely achieved through passive treatment alone. Passive care must be bridged with active movement. We encourage clients to engage in corrective exercises that support the work done on the table. Without neuromuscular re-education, muscles will often tighten again to provide artificial stability.

We also educate on the importance of “energy” efficiency in movement. A body that moves with aligned joints uses less metabolic energy and places less strain on ligaments. We may also suggest hand self-shiatsu for home care. Approaching pain massage as a partnership yields the best results.

For those interested in the professional application of these methods, the path requires dedication. A certification from RSM signifies that a therapist understands the intricate connections between the foot, the hip, and the spine. By addressing the root causes, we facilitate the body’s natural recovery process.

Mastering Assessment Protocols Used in Orthopedic Massage

Why Clinical Analysis Matters

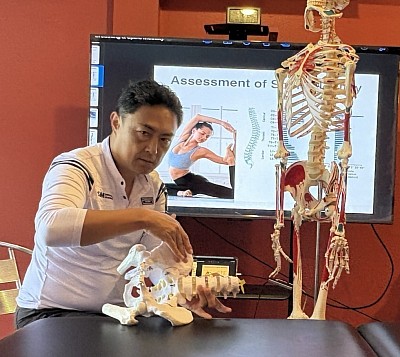

In the field of sports medicine and remedial therapy, precision dictates success. Many therapists approach a client’s pain with a general routine, simply rubbing where it hurts. However, pain is often misleading. The site of the symptom rarely matches the source of the dysfunction. At RSM, we operate differently.

I teach students in our Orthopedic Massage Course that effective massage treatment relies entirely on accurate evaluation. If a therapist skips the investigation phase, the resulting therapy is merely a shot in the dark. It might provide temporary relaxation, but it will not resolve the biomechanical root cause. To elevate massage from simple relaxation to clinical rehabilitation, we must use structured protocols that guide our hands.

The Foundation: Subjective Patient History

The investigation begins with the history. The subjective interview acts as the first filter for our clinical reasoning. A client might report shoulder pain. A novice hears “shoulder” and thinks of the rotator cuff. I listen for the timeline. If the client mentions a severe ankle injury three years ago, my attention shifts to the lower limb.

That previous injury likely caused a gait alteration. The altered gait reduced gluteal activation, forcing the latissimus dorsi to compensate for pelvic stability. Since the lats insert into the humerus, the shoulder pain is actually a result of lower-limb instability. Without this assessment information, we treat the victim, not the criminal.

Visualizing Posture and Muscle Imbalance

Once we understand the narrative, we observe the structure. Static posture analysis provides visual cues about long-term imbalances. Muscles reshape the skeleton over time. If a muscle remains hypertonic, it shortens and pulls attachment points closer together.

Consider a high right iliac crest. The lumbar spine side-bends to the right to compensate. This compresses the facet joints on one side while placing the opposing muscles under eccentric strain. The client feels pain on the strained side, but the true pathology is the pelvic obliquity. If we simply apply deep massage to the painful side without addressing the pelvic tilt, we risk destabilizing the spine further.

Active and Passive Mobility Evaluation

Visual inspection gives us a map; testing tests the terrain. We must differentiate between inert tissues (capsules, ligaments) and contractile tissues (muscles). To do this, we utilize specific tests.

We begin with Active Range of Motion (AROM). If pain occurs, it is non-specific. Therefore, we move to Passive Range of Motion (PROM), where I move the joint while the client relaxes. If pain disappears during passive movement, the issue is likely a muscle or tendon, as the contractile unit is at rest. This is a green light for soft tissue therapy. However, if the pain persists or we hit a hard mechanical block, we suspect a joint capsule issue, requiring mobilization rather than standard massage.

Performing Orthopaedic Tests and Functional Movement

Beyond range of motion, we utilize orthopaedic tests to stress specific structures. A McMurray’s test checks for meniscus tears; a Straight Leg Raise tests for neural tension. These allow us to rule out conditions requiring medical referral.

We also analyze movement under load. During an overhead squat, if the knees collapse inward (valgus), it indicates weak gluteus medius muscles. This dynamic analysis reveals the “why” behind the pain, guiding our remedial planning.

The Art of Palpation

We confirm our logic with palpation assessment. This is where the hands become diagnostic tools. We look for T.A.R.T.: Tenderness, Asymmetry, Restriction, and Texture.

When I palpate, I evaluate resting tone. Is the tissue hypertonic (tight) or hypotonic (weak)? Many massage therapists mistake eccentric loading for tightness. In Upper Cross Syndrome, the rhomboids feel taut because they are “locked long” by tight pectorals. Digging into them only weakens the back further. My palpation confirms the tension, but biomechanics directs the treatment to the chest.

Designing the Orthopedic Massage Protocol

The orthopedic assessment dictates the plan. At RSM, we do not use routine sequences. If we find a capsular restriction, we use joint mobilization. If we find fascial adhesion, we use myofascial release.

We differentiate based on the recovery stage. In the acute phase, we use lymphatic drainage to reduce inflammation. In the chronic phase, we use friction techniques to break down scar tissue. The goal is not just relief, but the restoration of proper joint movement.

The Cycle of Re-Evaluation

Clinical therapy is a continuous loop. We assess, we treat, and we re-evaluate. If I apply a massage technique to the psoas, I immediately re-test hip extension. If the range improves, the hypothesis was correct.

This validation process separates a technician from a specialist. At RSM International Academy, we believe that the quality of the therapy is defined by the quality of the assessment. Without a map, you are lost. With a proper assessment, you have a direct path to recovery.

A Guide to Choosing the Right Massage Specialty

The Impact of Specialization

Generalist practitioners often struggle to build sustainable practices. There are many possible reasons. A therapist who attempts to master every modality rarely achieves the clinical depth required to solve complex musculoskeletal issues. Clients experiencing chronic pain do not seek a generalist, they seek an expert capable of identifying the root cause of their dysfunction.

As a specialized massage school in Thailand, RSM structures its curriculum around this reality. We observe that graduates who select a focused track early in their education achieve higher client retention rates. They understand anatomy not just as a diagram, but as a functional map of levers and pulleys. When a client presents with lower back pain, a generalist might simply rub the erector spinae. A specialist, specifically one trained in our sports medicine methodology, looks for the anterior pelvic tilt, tight hip flexors, and weak glutes that define lower-cross syndrome.

Selecting a massage specialty is not merely a preference. It is a strategic business decision that dictates the longevity and profitability of your career.

Massage Therapy vs Relaxation

Students must distinguish between recreational bodywork and clinical therapy. Relaxation massage has its place in stress reduction, but it rarely addresses the mechanical pathologies we see in a clinical setting. Students drawn to the therapeutic side of the industry often find pure relaxation work unfulfilling. They prefer the puzzle of pathology. They want to know why a muscle is hypertonic, not just how to soothe it.

Sports massage is the cornerstone of the RSM approach. This is not simply deep pressure applied to an athlete. It is a systematic manipulation of soft tissue to correct imbalances caused by repetitive motion. Consider the mechanics of a runner. They frequently suffer from lateral knee pain. A novice might label this as a local knee issue. A specialist understands the kinetic chain. The tension often originates in the Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL), transmits through the iliotibial tract, and inserts at Gerdy’s tubercle. Treating the knee alone fails. Treating the TFL and correcting femoral mechanics succeeds.

Longevity and Biomechanics

Longevity in this field depends on biomechanics. Many therapists leave the profession within five years due to injury. They rely on thumb pressure and muscular effort rather than leverage and body weight. This is a failure of technique.

At RSM, Hironori Ikeda emphasizes a “therapist-first” approach to ergonomics. Deep work does not require self-sacrifice. When applying pressure to a dense structure like the gluteus medius, the therapist must stack their joints. They must generate force from their core and legs, not their wrists. A proper specialty education teaches you to use tools – elbows, knuckles, and forearms – to spare your thumbs.

The Science of Tissue and Assessment

To understand why specialization matters, one must understand the complexity of the soft tissue we treat. Muscles do not operate in isolation; they function in slings and chains. Effective therapy also respects the nervous system. “Deep” work that is too aggressive triggers a sympathetic response: fight or flight. The muscle tightens further to protect itself. We teach students to engage the parasympathetic system, using techniques that convince the nervous system to let go of the holding pattern.

You cannot treat what you cannot assess. Specialization requires mastery of orthopedic testing. Before a student touches a client at RSM, they perform a visual and functional assessment. We look for pelvic tilt, femoral rotation, and scapular position.

These observations dictate the treatment plan. If a client has an anterior pelvic tilt, we know the hip flexors are short and the hamstrings are long. We do not stretch the hamstrings, even if they feel tight. They are “locked long,” or eccentrically loaded. Stretching them further destabilizes the pelvis. Instead, we release the hip flexors to allow the pelvis to return to neutral. This logic is counter-intuitive to the untrained therapist, but second nature to the specialist.

The Financial Reality of Massage Therapy

Specialists command higher fees. The market recognizes skill. A therapist who can resolve a frozen shoulder or alleviate sciatica provides immense value. Clients are willing to pay a premium for results. In contrast, the general relaxation market competes on price. By choosing a niche in sports and rehabilitation, you remove yourself from the race to the bottom. You compete on quality and outcomes.

Choosing Massage Styles for a Career

The industry needs more thinkers. It needs more therapists who look at a swollen ankle and ask about hip stability. If you are content with a basic routine, a generalist path suffices. If you demand excellence from yourself and results for your clients, you must specialize.

At RSM International Academy, we provide the tools, the knowledge, and the mentorship.

Understanding the Functional Differences Between Massage Modalities

Defining the Scope of Modern Massage Therapy

At RSM International Academy, we view the body as a biological machine. When students in our Deep Tissue Massage Course ask about the differences between massage modalities, they often expect a comparison of relaxation versus intensity. However, the distinction is mechanical. To be an elite therapist, you must understand the physiological chain of events your hands initiate.

When a client experiences chronic pain, the issue is rarely isolated. A biomechanical dysfunction triggers a protective spasm. This spasm reduces blood flow, causing hypoxia. Hypoxia creates acidity, which stimulates pain receptors. To treat this, we cannot simply rub the skin. We must intervene at the correct link in this chain.

Different massage styles intervene at different points. Some target the nervous system; others target fascial layers. Consequently, the massage therapy you choose determines the biological outcome. Knowing why you are touching a structure is more important than knowing how to touch it.

The Science Behind Various Massage Styles

To categorize massage, we look at the intent of the treatment. We generally divide bodywork into circulatory, structural, and neuromuscular categories.

Circulatory approaches, specifically Swedish massage, rely on venous return. Centripetal strokes push blood toward the heart. This increases cardiac preload, improving systemic circulation. Better circulation flushes metabolic waste, leading to reduced muscle tension.

In contrast, structural approaches focus on architecture. Deep tissue massage and myofascial release fall here. The goal is tissue elongation. Under sustained pressure, fascia changes from a gel to a fluid state. This restores the range of motion.

Neuromuscular approaches target the nerve-muscle connection. Techniques like trigger point therapy interrupt the pain-spasm cycle. We apply ischemic compression to cut off blood supply to a contracted sarcomere. Releasing the pressure floods the area with fresh blood, resetting the neuromuscular junction.

The type of massage dictates the mechanism. A skilled massage therapist switches tools instantly to suit the health needs of the client.

Swedish Massage vs. Structural Approaches

Swedish massage is the foundation of relaxation, but its effects are clinical. The technique stimulates skin mechanoreceptors, signaling the brain to downregulate the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight). This lowers cortisol and systemic inflammation.

However, Swedish massage glides over fascia rather than engaging it. Structural styles differ. In structural work, we hook onto the tissue barrier. This engages the piezoelectric effect, generating a charge that signals fibroblasts to reorganize collagen. Over a session, this can reshape posture. Swedish massage relaxes muscles, but structural work realigns them.

Deep Tissue Massage and Neuromuscular Mechanisms

A pervasive myth suggests deep tissue massage is just Swedish massage with more force. Anatomically, this is incorrect. Deep tissue refers to the layer we target, not just the force we apply.

To access deep musculature like the quadratus lumborum, we must first relax superficial layers. If we apply heavy force immediately, the superficial muscles guard. Deep tissue massage requires a slow, sinking engagement to shear adhesions between muscle fibers. This restores the ability of muscle groups to slide past one another.

This leads to neuromuscular massage. While deep tissue focuses on layers, neuromuscular techniques focus on trigger points—hyper-irritable spots referring pain. We apply static pressure to create local ischemia. Upon release, a hyperemic response washes away pain-sensitizing chemicals. For therapists treating chronic pain, mastering this distinction is essential.

The Biomechanics of Thai Massage

Living in Chiang Mai, I respect Thai massage for its leverage systems. Unlike Western massage styles where the client is passive on a table, Thai massage uses yoga-like positioning on a mat.

The biomechanics are distinct. Passive stretching activates Golgi Tendon Organs (GTOs). GTOs detect tendon tension and inhibit muscle contraction to prevent tearing. By moving the client, the therapist utilizes these reflexes to gain range of motion.

Specific techniques utilize the practitioner’s body weight. Instead of using thumb muscles, I transfer force from my core. This results in deep, consistent pressure without practitioner fatigue.

Clinical Massage and Medical Applications

Clinical massage is a methodology, not just a technique. In a medical context, perhaps alongside a chiropractic doctor, our goal is functional improvement.

A session begins with assessment. We formulate a hypothesis—for example, tight hip flexors causing lumbar compression. The treatment focuses on lengthening specific muscles. We re-test immediately. If the range of motion improves, our hypothesis is confirmed.

This analytical approach differentiates a medical massage therapist from a spa practitioner. A chiropractic adjustment aligns bone, but if soft tissue remains tight, it pulls the bone back out of alignment. Soft tissue therapy is often the missing link.

Specialized Techniques: Lymphatic and Shiatsu

Lymphatic massage (or drainage massage) targets the lymphatic system, which relies on pressure changes to move fluid. Standard massage pressure collapses fragile lymphatic capillaries. Therefore, lymphatic massage uses extremely light traction to open capillaries and reduce edema.

Conversely, shiatsu massage applies rhythmic, static pressure to points corresponding to nerve bundles. This rocking motion stimulates the vestibular system, promoting deep relaxation distinct from deep tissue.

Integration and Training

The body adapts. If we use the same techniques, tissue builds tolerance. A therapist limited to one style cannot treat complex cases. A therapist only knowing deep tissue may injure a fibromyalgia patient.

At RSM, we emphasize that styles are tools. A session might start with Thai massage stretches, transition to deep tissue on the back, and end with lymphatic strokes. Integrating these differences between massage modalities leads to superior health outcomes.

Training determines your trajectory. You need training that explains the “why.” At RSM International Academy, we dissect these differences so graduates become engineers of the human body. Whether drawn to sports massage, the precision of Thai massage, or structural work, the foundation must be scientific.

By mastering the functional differences between massage modalities, you position yourself as a leader in wellness. The journey requires dedication, but the ability to resolve pain is the ultimate reward.

Trigger Point Therapy for Athletes: A Sports Medicine Approach

Understanding the Science of Trigger Point Therapy

A common misconception is that muscle stiffness is always just “tightness.” In fact it is often a microscopic physiological error. Inside the muscle fiber, actin and myosin filaments lock together due to an excessive leak of acetylcholine. This sustained contraction compresses local capillaries, cutting off oxygen and trapping metabolic waste. The result is an acidic, ischemic environment that sensitizes pain receptors. We clinically define this hypersensitive nodule as a trigger point.

Trigger point therapy is not merely applying pressure; it is the reversal of this ischemia. By applying precise compression, as taught in our Trigger Point Therapy Course, we temporarily halt blood flow. Upon release, a hyperemic response floods the tissue with oxygenated blood, flushing out the acidic waste and allowing the sarcomere to unlock. This restores the muscle to its functional resting length.

How a Trigger Point Affects Biomechanics

A single nodule can destabilize an athlete’s entire kinetic chain. When a muscle harbors a trigger, it becomes functionally shorter and weaker. This forces surrounding structures to compensate, leading to injury far from the original site.

Consider a runner with a latent trigger in the soleus. This shortened calf muscle limits ankle dorsiflexion. To maintain forward momentum, the foot must pronate excessively, which forces internal tibial rotation and alters patellar tracking. As a result, athletes report lateral knee pain. A standard therapist might treat the knee, but at RSM, we treat the calf. The pain is the symptom; the restriction in the lower leg is the cause.

If we fail to map these referral patterns, treatment fails. An active trigger in the gluteus minimus often mimics sciatica, sending signals down the leg. By differentiating between nerve entrapment and a myofascial trigger, we ensure the body receives the correct intervention.

Differentiating Dry Needling from Manual Techniques

In modern sports medicine, techniques like dry needling have gained popularity. This involves inserting a monofilament needle into the taut band to elicit a spinal reflex that resets the muscle. While effective, invasive methods are not always the optimal starting point. Needling can cause significant post-treatment soreness, which may interfere with an athlete’s immediate schedule.

In contrast, manual trigger point massage offers diagnostic feedback that needles cannot. Through palpation, I assess tissue hydration, temperature, and fascial texture. While medical professionals may use point injections to numb the area, this masks the body’s feedback mechanisms. Manual therapy modulates the nervous system, reducing sympathetic tone and promoting the parasympathetic state required for deep recovery.

Integrating Trigger Point Massage into Training

Timing is critical. I teach my students that deep trigger point massage should never be performed immediately before a competition. Releasing a restriction drops muscle tone and alters proprioception. An athlete who feels “too loose” loses the elastic tension necessary for explosive performance.

Instead, we integrate this work during recovery phases. The goal is to maintain the ideal length-tension relationship in the muscles. A muscle at optimal resting length generates peak force; a shortened muscle creates less torque and fatigues rapidly. Therefore, pain relief is secondary to mechanical efficiency.

We also analyze sports specificity. Cyclists often develop shortened hip flexors, while pitchers overload the posterior shoulder. Recognizing these patterns allows us to treat trigger points proactively.

Common Athletic Trigger Sites:

- Upper Trapezius: Elevated by stress; refers pain to the head.

- Quadratus Lumborum: Strained by lifting; refers to the hip.

- Soleus: Shortened by running; refers to the heel.

Mastering Point Therapy for Long-Term Results

The difference between a silver and gold medal often lies in biomechanical efficiency. By understanding the physiology of myofascial trigger points, we move beyond treating symptoms and address the root of dysfunction. Whether using physical therapy modalities or manual compression, the objective remains the same: restore flow and function.

At RSM, we view the trigger as a map of the athlete’s history: their loads, compensations, and stress. Trigger Point therapy is the tool we use to read that map. When a therapist masters this logic, they stop just rubbing muscles and start optimizing the human machine for peak physical output.

Advanced Orthopedic Massage Techniques in Modern Therapy

Clinical Precision in Bodywork

In my years of clinical practice I have often observed practitioners treating symptoms rather than systems. They rub the area that hurts. However, pain is rarely a local event; it is the final signal in a chain of biomechanical failures. This distinction drives our Orthopedic Massage Course. We do not just teach students to rub tissues; we teach them to act as clinical investigators.

Defining Orthopedic Massage in Practice

Orthopedic massage is not a singular modality but a comprehensive system of assessment and treatment. It focuses on correcting soft tissue conditions and structural dysfunctions that restrict function. Unlike a standard spa session, where the goal is sedation, this approach utilizes a multidisciplinary framework. It integrates anatomy and biomechanics to restore balance.

When a client presents with a complaint, the massage is secondary to the assessment. For example, if the gluteus medius is inhibited, the Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL) often compensates, creating lateral knee pain. A therapist who only rubs the knee will fail. The therapy must address the inhibited gluteal muscle and the hypertonic TFL to resolve the issue permanently.

This clinical precision is what separates a relaxation provider from a highly skilled massage therapist. We focus on the restoration of capability. By manipulating the structures that surround the skeletal frame, we can alleviate chronic holding patterns that lead to pathology.

Core Massage Techniques for Restoration

To achieve these structural changes, we employ specific manual interventions. These massage techniques address specific physiological layers, ranging from breaking down adhesions to resetting neuromuscular tone.

We utilize the following approaches:

- Deep Tissue Massage: True deep tissue massage involves sinking through the superficial fascia to access sub-layer musculature. We teach students to melt through layers, engaging the structure without forcing it.

- Tissue Mobilization: This involves scooping and shearing forces to separate stuck tissue layers. Effective tissue mobilization restores the ability of individual muscles to slide past one another.

- Muscle Energy Techniques (MET): Using active contraction against resistance to lengthen shortened tissues without aggressive stretching.

These tools allow the therapist to remodel tissue. This is particularly relevant for sports injuries orthopedic specialists diagnose, such as tendonitis. We physically alter the structural composition of the tendon to encourage healing.

Restoring Mobility Through Joint Action

Soft tissue work alone is sometimes insufficient. The relationship between the contractile unit and the joint is symbiotic. Therefore, orthopedic massage must address joint mechanics.

At RSM, we emphasize joint mobilization. This is not chiropractic adjustment, but the gentle oscillation of articular surfaces. For instance, “frozen shoulder” involves a restriction in the joint capsule. While working on the rotator cuff is helpful, it does not address the capsular restriction. By integrating gentle joint mobility work, we create the space for mechanics to normalize.

This integration defines the advanced therapy we practice. It signals to the nervous system that the range of motion is safe, allowing the brain to reduce protective guarding.

Case Studies: Treating the Lower Back

Low back pain is perhaps the most common complaint we encounter. In many cases, the Quadratus Lumborum (QL) is blamed. However, treating the QL is often treating the victim, not the criminal.

The QL often becomes hypertonic because the Gluteus Medius is weak. If the glute fails to stabilize the pelvis, the QL works overtime. Digging an elbow into the QL offers only temporary relief. The treatment must involve releasing the QL followed immediately by activation work for the glutes.

Another culprit is the Psoas Major. A tight Psoas pulls the spine into hyper-lordosis, compressing the lumbar region. Here, the therapy involves deep abdominal work. The relief is often instantaneous as the lumbar curve settles into alignment.

The RSM Approach to Treatment

At RSM, we train students to see the body as a tensegrity structure. When one strut fails, the network shifts. Orthopedic massage is the science of identifying that primary failure.

Our approach bridges the gap between manual therapy and rehabilitation. We often recommend corrective exercises to support the manual work, ensuring patients do not become dependent on the therapist. Whether treating athletes or clients recovering from surgery, the goal is autonomy.

Musculoskeletal issues evolve based on how the body is used. Consequently, the treatment plan must adapt. Many styles of massage orthopedic practitioners favor focus on symptoms; we focus on solutions. By mastering these orthopedic techniques, therapists position themselves as essential healthcare providers. This is the standard we uphold at RSM.

The Science of Improving Mobility with Myofascial Release

At RSM International Academy, we frequently encounter students and clients who confuse flexibility with mobility. They assume that an inability to touch their toes indicates short hamstrings, leading them to stretch aggressively. Yet, the stiffness often remains. This stagnation usually stems from a misunderstanding of the body’s architecture. The limitation is rarely a lack of muscular length; it is often a loss of sliding potential within the fascial tissues.

My approach, grounded in my background as an MSc in Sports Medicine, focuses on the causal chains that restrict movement. True mobility requires the independent gliding of muscles, nerves, and vascular structures. When these structures adhere due to trauma or overuse, standard stretching is ineffective. Instead, as we teach in our Dynamic Myofascial Release Course, we must focus on increasing mobility by addressing the connective architecture directly.

Understanding Myofascial Release Mechanisms

To understand why mobility is lost, we must look at the fascial tissues. Fascia is a continuous, three-dimensional matrix lubricating every muscle and organ with Hyaluronan. Under normal conditions, layers slide effortlessly. However, mechanical stress transforms this lubricant into a glue-like substance, a process known as densification.

This adhesion creates a mechanical barrier. When a patient attempts to move, the internal structures cannot slide. The brain perceives this resistance and inhibits muscle activation. Myofascial release works by applying sustained shear force to these densified areas. The friction reduces the viscosity of the hyaluronan, restoring the gliding potential of the soft tissue. Once the layers separate, the range of motion improves immediately.

Addressing Chronic Muscle Tension

It is critical to distinguish between neurological tightness and mechanical restriction. In our clinic, we see many clients with chronic “tight shoulders” who find no lasting relief from standard massage. They treat the symptom—the tension—without addressing the container—the fascia.

Muscle tension is often a protective response. When the fascial envelope becomes rigid, it acts like a shirt that is two sizes too small. The muscle fibers inside are compressed, leading to ischemia (lack of blood flow). This oxygen deprivation causes the muscle to contract further, creating a cycle of pain. Standard massage presses the muscle against the bone, which fails to expand the “shirt.” In contrast, manual therapy aiming for structural integration elongates the fascial planes. By expanding the container, we remove the mechanical compression, and the pain signals dissipate.

The Role of Trigger Points

Mobility is also compromised by trigger points—specific physiological lesions within skeletal muscle. A trigger point forms when a metabolic crisis locks actin and myosin filaments into a continuous contraction. This cuts off local oxygen supply, creating an acidic environment that sensitizes pain receptors.

A trigger point in the hip, for example, can mimic sciatica. In our therapy courses, we teach students to use ischemic compression to treat these spots. By temporarily blocking and then releasing blood flow, we flush the tissue with oxygen, breaking the metabolic crisis. This restores the muscle’s ability to lengthen, thereby improving mobility with myofascial release.

Self-Myofascial Release vs. Manual Therapy

The fitness industry has popularized self-myofascial release using foam rollers. While myofascial rolling is valuable for warming up or resetting neural tone, it has limitations. A foam roller applies broad compression; it cannot distinguish between nerve entrapment and fascial adhesion.

Mechanical restrictions often require a specific vector—a direction of pull—to release. A skilled therapist uses their hands to hook into the body and apply precise shear force. Furthermore, rolling requires active muscle contraction to stabilize the body, whereas manual therapy allows the patient to remain passive. This passivity grants the therapist access to deeper myofascial layers that are inaccessible when muscles are engaged.

Restoring Functional Capacity

The ultimate goal of any therapy at RSM is not just temporary pain relief, but the restoration of function. Pain is merely the signal; dysfunction is the problem.

Consider a runner with lower back pain. The cause is often adhered hip flexors preventing hip extension. This forces the lumbar spine to over-extend to compensate. Treating the back offers only temporary relief. The solution requires a targeted fascia release of the Psoas. By freeing the hip, we spare the spine.

At RSM, we teach release techniques that respect the thixotropic nature of fascia. We do not force the tissue; we sink and wait for the body to yield. This approach ensures that we are not just relaxing the patient, but permanently improving their biomechanics. Through the intelligent application of myofascial release, we provide a pathway to a mobile, functional, and pain-free life.

Sports Massage Assessment Techniques: Mastering Clinical Precision

In manual therapy, technical skill in delivering strokes is only half of the equation; true clinical effectiveness comes from structured assessment grounded in biomechanics, functional anatomy, and the behavior of the kinetic chain. At RSM International Academy, practitioners in our Sports Massage Course learn that moving beyond a basic intake form into orthopedic-grade evaluation elevates the precision of their therapy.

While research on manual therapy’s influence on kinetic-chain mechanics is still developing, clinical practice and movement analysis consistently indicate that understanding joint mechanics and tissue responsiveness before treatment improves the relevance and accuracy of manual interventions. This evidence-informed approach establishes a professional standard where each session is intentional, targeted, and aligned with the client’s specific performance demands.

Subjective Evaluation: The Interview

The assessment begins with the investigative phase. While beginners may simply ask, “Where does it hurt?”, the intermediate therapist uses structured questioning to understand the mechanism of injury. Is the condition acute, sub-acute, or chronic? This classification controls treatment intensity; for example, deep friction is contraindicated in the acute inflammatory phase. To accurately profile pain, therapists apply the OPQRST framework (Onset, Provocation, Quality, Region, Severity, Timing).

At RSM International Academy, this process also includes identifying pain-avoidance posture and antalgic lean, recognizing how clients unconsciously change alignment to escape pain. This helps determine which movements in the kinetic chain trigger symptoms and which joints are absorbing excess load. By integrating these observations, the interview becomes more than a checklist—it becomes a clinically meaningful analysis that guides precise and targeted manual therapy.Objective and Visual Analysis

Once the history is taken, we move to objective observation using the “Plumb Line” approach. Visual analysis identifies kinetic chain imbalances that contribute to dysfunction.

- Anterior View: Check for knee valgus or leg length discrepancies.

- Lateral View: Crucial for spinal evaluation. Look for Forward Head Posture (FHP) or Anterior Pelvic Tilt, which dictates whether you need to lengthen hip flexors or hamstrings.

- Posterior View: Observe scapular positioning and Achilles tendon alignment.

Functional Evaluation: Range of Motion (ROM)

Static posture gives us a map, but the body is designed for movement. Functional assessment tests the integrity of specific tissues:

- Active ROM (AROM): The client moves the joint unassisted. Pain here indicates muscle strain or joint issues.

- Passive ROM (PROM): The therapist moves the relaxed limb. If AROM is painful but PROM is pain-free, the issue is likely muscular (contractile tissue). If PROM is also painful, the issue may be articular (ligament/capsule).

- Resisted ROM (RROM): Testing isometric strength to identify lesions in the muscle-tendon unit.

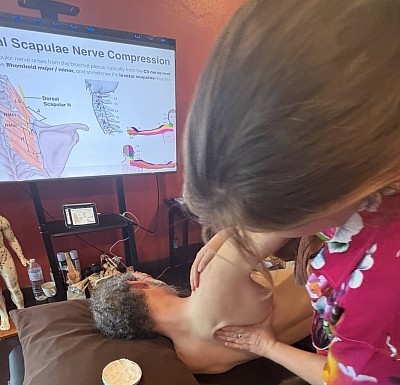

Palpation and Special Tests

While visual and functional tests provide data, palpation is where the massage therapist truly shines. Clinical palpation requires differentiating tissue states—distinguishing between hypertonicity (tight muscle), fibrosis (scar tissue), and edema (swelling).

To truly specialize in sports care, you must also be familiar with “Special Tests.” These provocative maneuvers stress specific structures to identify pathology. Examples include:

- The Empty Can Test: Assesses the Supraspinatus tendon for rotator cuff tears.

- The Thomas Test: Differentiates tightness between the Iliopsoas, Rectus Femoris, and TFL.

- Ober’s Test: Identifies tightness in the IT Band, crucial for runners with knee pain.

Mastering Sports Massage Improves Performance and Recovery

Advanced sports massage evaluation techniques allow you to navigate complex musculoskeletal issues with confidence. By linking assessment data directly to your treatment plan, such as releasing a fibrotic TFL to cure lateral knee pain, you ensure that your therapy is purposeful and effective.

For the therapist, the journey involves moving beyond intuition and embracing a systematic, evidence-based approach. By integrating detailed history taking, functional ROM testing, and specific orthopedic evaluations, you provide a higher standard of care that leads to faster recovery and better performance outcomes for your clients.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

Reference

1) HL Davis et al. (2020). Effect of sports massage on performance and recovery. PMC.

2) B Liza et al. (2023). Effectiveness of manipulative massage therapy in pain, ROM and shoulder function (pdf).

The Difference Between Sports and Deep Tissue Massage

For individuals dealing with chronic pain, limited mobility, reduced flexibility, or a limited range of motion, the terminology used in rehabilitation and wellness can easily become confusing. Two treatments that often seem similar on the surface are sports massage and deep tissue massage, mainly because both aim to relieve physical discomfort. In reality, their purposes and physiological focus are very different. Deep tissue massage addresses postural deviation, chronic holding patterns, and deeper layers of muscle and connective tissue—work that improves movement quality and long-term structural alignment. Sports massage, on the other hand, is closely connected to sports conditioning management, performance readiness, and maintaining optimized movement for active individuals.

At RSM International Academy, our Sports Massage Course emphasizes understanding when and why each modality should be applied. Using deep tissue techniques to correct alignment and resolve adhesions is not the same as using sports massage to support recovery, manage training load, or maintain functional biomechanics. Whether you are a client seeking treatment or a therapist in training, recognizing this distinction leads to more accurate injury management and more consistent improvements in optimized movement and overall body mechanics.

What is Deep Tissue Massage?

Deep tissue massage is a structural integration approach, and in the RSM method it is also used to restore joint centralization and improve kinetic chain alignment. Although it is often mistaken for “a very hard massage,” true deep tissue work depends on precision, myofascial layering, and understanding how deeper structures influence posture and movement, not on force. The goal is to resolve chronic strain, postural deviation, and misalignment within the kinetic chain by targeting the deeper layers of muscle and connective tissue while enhancing overall movement quality.

During our Deep Tissue Massage Course the therapist uses slow, deliberate strokes to move from the superficial into the deep myofascial layers, focusing on muscle glide, intermuscular mobility, and tension patterns without provoking protective tightening. Sustained pressure with knuckles, elbows, and forearms helps break down adhesions and scar tissue, while equal emphasis is placed on therapist positioning, the direction of applied pressure, and the mechanics required to reach deeper structures. In the RSM system, deep tissue work not only releases chronic holding patterns—such as a stiff neck, low-back tightness, or forward head posture—but also improves joint centralization and optimizes kinetic chain alignment, leading to more efficient and pain-free movement.

What is Sports Massage?

The RSM Sports Massage Course teaches a targeted and dynamic method rooted in biomechanics and sports-related injuries, designed for anyone who places continuous physical stress on the body. This approach emphasizes sports conditioning management, focusing on maintaining joint mobility, tissue elasticity, and proper kinetic-chain alignment throughout training cycles. Techniques adapt to purpose—pre-event work activates the neuromuscular system, post-event work clears metabolic waste, and maintenance work preserves movement efficiency and performance.

A key element of the RSM method is the integration of active components, including stretching, joint mobilization, and muscle-energy techniques. These tools are applied to improve kinetic-chain function, support joint-mechanics centralization, restore tissue elasticity, and keep the body performing efficiently under physical demand. The goal is not simply relaxation, but maintaining the body as a functional system capable of consistent performance.

Key Differences in Intent and Massage Techniques

The divergence between the two lies in the intent of the session.

- Speed and Rhythm: Deep tissue is slow. To sink into the deep layers of the body, the therapist must wait for the tissue to melt. Sports massage varies in tempo and is often brisk to stimulate blood flow and nervous system response.

- The Focus: Deep tissue is problem-oriented regarding chronic pain and structure. It asks, "How does your posture affect your pain?" Sports massage is outcome-oriented. It asks, "How does this muscle tension affect your running stride or your squat?"

- Passive vs. Active: In deep tissue, the client is usually passive. In sports massage, the client is often active, moving limbs against resistance to engage the nervous system.

Which Do You Need: Sports Massage or Deep Tissue Massage?

If your goal is to fix long-term postural issues, relieve chronic back pain from sitting, or break up old scar tissue, deep tissue massage is the correct choice. It releases the tension that pulls the body out of alignment.

If your goal is to recover from a workout, improve your flexibility for a specific sport, or prevent injury during training, sports massage is the superior option. It focuses on keeping the soft tissues elastic and responsive.

The RSM Approach for Aspiring Massage Therapists

Ultimately, the most effective treatment often requires a blend of both. A massage therapist trained at RSM International Academy learns to integrate these styles based on clinical assessment. We teach our students that you cannot effectively perform either modality without a profound understanding of functional anatomy and clinical palpation. By bridging the gap between these techniques using sports medicine principles, we ensure that every massage is a step toward better health, posture, and performance.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

References

1) Dakić, M., Toskić, L., Ilić, V., Durić, S., Dopsaj, M., & Šimenko, V. (2023). The Effects of Massage Therapy on Sport and Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports (Basel). [PMC]

2) Jones, T. A. (2004). Rolfing, or Structural Integration: A Review of the Evidence. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies. [PubMed]

Cluneal Neuralgia or Piriformis Syndrome? How to Differentiate SI Joint Pain, Deep Gluteal Syndrome and Sciatica

In clinical sports medicine, not all buttock pain is sciatica. A relatively overlooked cause is cluneal neuralgia, particularly entrapment of the middle cluneal nerve beneath or through the long posterior sacroiliac ligament (LPSL). This often produces a superficial burning or stabbing sensation around the posterior iliac crest and upper buttock, closely resembling sacroiliac joint dysfunction or lumbar radiculopathy but not following a typical dermatomal distribution.

To distinguish cluneal neuralgia from piriformis syndrome and deep gluteal syndrome, I first differentiate between superficial cutaneous pain and deep myoneural pain. Palpation along the PSIS and the LPSL often reproduces symptoms associated with middle cluneal nerve entrapment. In contrast, deep pressure at the greater sciatic notch and along the short external rotators evokes a deeper stretching or radiating pattern consistent with sciatic or posterior femoral cutaneous nerve involvement. The FABER (Patrick) test helps determine whether the sacroiliac joint itself is the primary pain generator or if symptoms stem from periarticular ligament or nerve irritation.

Anatomically, the superior gluteal nerve and vessels pass above the piriformis through the suprapiriform foramen, while the sciatic nerve, inferior gluteal nerve and posterior femoral cutaneous nerve pass below it through the infrapiriform foramen. Variations in the course of the sciatic or posterior femoral cutaneous nerve, such as splitting or piercing the piriformis, explain why some athletes present with atypical deep gluteal pain that does not follow standard textbook patterns. Palpation landmarks such as the PSIS–greater trochanter line and the greater sciatic notch are useful, but it is important not to mistake the overlapping upper fibers of gluteus maximus and gluteus medius for the piriformis itself.

Once the primary pain source is identified, treatment becomes more precise. For cluneal neuralgia, the focus is on accurate palpation of the LPSL, releasing superficial fascial restrictions and reducing irritation around the nerve pathway. For piriformis syndrome and deep gluteal syndrome, cross-fiber soft-tissue mobilization, active mobilization of the piriformis and the deep external rotators and nerve-gliding techniques for the sciatic and posterior femoral cutaneous nerves help restore mobility in the greater sciatic notch region. This anatomical and layer-specific approach consistently produces better outcomes than generalized deep tissue massage.

If you want to study the palpation skills, pain differentiation, and clinical treatment strategies in greater depth, you can learn them in our Trigger Point Therapy and Deep Tissue Massage programs at RSM International Academy.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

References

1)Anderson D. A comprehensive review of cluneal neuralgia as a cause of low back pain. 2022.

2)Martin HD, Reddy M, Gómez-Hoyos J. Deep Gluteal Syndrome: anatomy, imaging, and management of sciatic nerve entrapments in the subgluteal space. 2015.

Heel-Strike Dominance, Tightness in the Posterior Gluteal Fibers, and the Role of the Superior Cluneal Nerve

Clients who land heavily on their heels often present with clear tightness in the posterior fibers of the gluteus medius and the upper fibers of the gluteus maximus. Therapists encounter this pattern repeatedly, especially in individuals whose pelvic control relies heavily on these muscles to absorb the shock generated at heel strike. As these muscles tense over time, fascial glide decreases, creating persistent stiffness and trigger points around the upper and lateral gluteal region.

An important but frequently overlooked factor in this pattern is the Superior Cluneal Nerve. Originating from the dorsal rami of L1 to L3, the nerve passes through the thoracolumbar fascia, crosses the quadratus lumborum and multifidus, and travels over the iliac crest near the PSIS before entering the upper gluteal area. This region along the iliac crest is particularly prone to entrapment. When the nerve becomes restricted, discomfort and radiating tension across the upper gluteal region can worsen, especially when the surrounding musculature is already overworked.

People who show mild Trendelenburg-type pelvic drop during gait often display not only muscle tension but also decreased neural mobility in this area. This makes the pelvis less stable with each step, not simply because of muscle weakness, but due to a combination of neural entrapment and fascial tension around the posterior hip. Athletes who engage in running, golf, or rotational sports commonly develop this pattern.

At RSM International Academy, practitioners study these gluteal and neural interactions in detail through Trigger Point Therapy and Deep Tissue Massage. The approach includes deep release of the posterior gluteus medius, targeted treatment of upper gluteus maximus trigger points, and techniques aimed at restoring mobility around the superior cluneal nerve near the iliac crest. Improving the glide of the deep fascial layers in this region consistently helps reduce low-back discomfort and upper gluteal pain, making it a highly reliable treatment zone.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

References

1) Maigne JY, Doursounian L. Entrapment neuropathy of the superior cluneal nerves. Spine. 1997;22(10):1156–1159.

2) Lu J, Ebraheim NA, Huntoon M, et al. Anatomic considerations of the superior cluneal nerve at the posterior iliac crest region. Clin Anat. 2000;13(3):139–143.

Kinetic Chain Dysfunction as the Hidden Driver of Forearm Pain

Forearm pain, especially Pronator Teres Syndrome and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, is frequently misinterpreted as a localized forearm disorder. From a sports medicine perspective, however, these symptoms most often arise from disruptions within the kinetic chain linking the glenohumeral joint, the forearm, and the wrist. The essential biomechanics of the upper limb are organized into two primary movement pathways:

1. GH Internal Rotation → Forearm Pronation → Wrist Ulnar Deviation

2. GH External Rotation → Forearm Supination → Wrist Radial Deviation

When mobility restriction or neuromuscular dysfunction occurs at any point along these pathways, deep forearm muscles such as the pronator teres, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor digitorum profundus contract excessively as a compensatory strategy. This pattern significantly increases the likelihood of Median Nerve Glide Dysfunction, a mechanism consistently supported by sports medicine literature.

A particularly common clinical finding is reduced external rotation capacity of the rotator cuff, specifically the infraspinatus and teres minor. Movements that should be absorbed through GH external rotation are instead diverted into excessive forearm pronation, leading to chronic overactivation of the pronator teres and deep flexor group. This compensation pattern—GH ER restriction → increased forearm flexor tone → neural mobility impairment—is one of the most reproducible mechanisms observed across clinical practice.

This phenomenon is clearly visible in various sports settings.

Judo gripping actions require repeated traction and rotation with the wrist fixed, dramatically elevating pronation load. Martial arts impose continuous gripping and rotational acceleration, producing chronic fatigue in the deep flexor–pronator complex. Yoga handstands fix the wrist under load, increasing isometric tension in the forearm. Baseball pitching, the golf downswing, and tennis forehand strokes all involve pronounced pronation combined with ulnar deviation, making pronator teres stiffness highly prevalent among athletes.

The common denominator across these activities is that the wrist remains mechanically locked while compensatory load concentrates in the forearm, leading to progressive myofascial adhesions and deterioration of median nerve mobility. Localized treatment alone rarely produces lasting improvement because it overlooks the integrated nature of the upper-limb kinetic chain.

At RSM International Academy, directed by Hironori Ikeda, clinical assessment centers on the shoulder–forearm–wrist kinetic chain. The academy emphasizes comprehensive evaluation of GH external rotation restriction, scapular motion control, restoration of median nerve mobility through nerve-glide techniques, dynamic myofascial release of deep fascial structures, and high-level palpation skills indispensable for differentiating fiber orientation, fascial density, and neural pathways. Palpation training is directly integrated with functional anatomy to enable precise identification of the pronator teres, FDS, and FDP complexes.

When GH external rotation improves, compensatory forearm activation naturally diminishes, reducing hypertonicity even during tasks requiring wrist fixation. This represents the restoration of the authentic kinetic chain, producing stable and long-lasting clinical outcomes.

These concepts and techniques are systematically explored within the

1) Sports Massage Course,

2) Remedial Massage Course,

3) Dynamic Myofascial Release Course at RSM International Academy.

Each course is grounded in the sports medicine principle that the upper limb must be evaluated as a single functional movement system rather than isolated anatomical segments.

Ultimately, forearm pain, neural symptoms, and shoulder dysfunction may appear unrelated, yet when viewed through the kinetic chain, they align along a single continuum. A whole-chain perspective yields the most accurate, reproducible, and clinically valid approach in sports medicine.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

References

1) Ludewig PM, Reynolds JF. The Association of Shoulder Dysfunction with Upper Extremity Nerve Entrapment Syndromes: A Kinematic Perspective. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.

2) Werner SL, Fleisig GS, Dillman CJ, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of the Elbow and Forearm During Sports Activities. Clinical Sports Medicine.

Patellar Fat Pad Impingement and Kinetic Glide Chain Restoration: Clinical Approach to Chronic Anterior Knee Pain

In clinical practice, anterior knee pain rarely stems from a single cause. When careful work on the patellar tendon or quadriceps tendon yields little improvement, the true source is often found behind the patella — within the infrapatellar fat pad (Hoffa’s fat pad).

This fat pad serves as a cushion for the knee, but when it becomes repeatedly compressed between the inferior pole of the patella and the anterior tibia, it can develop fibrosis and adhesions, leading to a condition known as Patellar Fat Pad Impingement. Chronic cases or post-meniscal injuries often present with this pattern, accompanied by a loss of superior–inferior patellar glide and deep anterior knee discomfort.

My initial clinical evaluation is straightforward yet highly informative. With the thumb stabilizing the inferior border of the patella and the index finger supporting the superior border, I gently mobilize the patella in all directions — superior, inferior, and circular motions — to assess tissue elasticity and fibrotic resistance.

When a “gritty” friction or marked discomfort is felt, I apply micro-mobilization combined with deep transverse friction while maintaining slight knee flexion (15–20°). The goal is to guide the fat pad posteriorly during flexion and allow smooth anterior glide during extension. As the tissue softens, patellar motion becomes smoother, and the patient often reports a clear release of the deep “pressure” sensation behind the knee.

A crucial element is correcting the lateral pulling tension that perpetuates this problem. In most cases of chronic patellar pain, excessive tension within the Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL), Iliotibial Band (ITB), and Vastus Lateralis forms a dominant lateral kinetic chain that drags the patella laterally.

To release this, I first perform longitudinal fascial release along the Rectus Femoris–Vastus Intermedius interface, followed by cross-fiber release at the distal one-third. Next, I restore the mobility of the suprapatellar pouch through ASTR (Active Soft Tissue Release). Once these layers regain glide, patellar tracking improves and the kinetic glide chain reorganizes naturally.

At this point, I also check the function of the Popliteus muscle, which contributes to the screw-home mechanism of the knee. By gently activating this muscle in slight flexion, we can reestablish end-range rotational stability and centralize patellar tracking. Correcting the lateral drift not only reduces pain but also restores structural balance across the patellofemoral joint.

In many of my clinical cases, after about four to five sessions (roughly two weeks), patients show clear improvement: pain on stair climbing decreases from NPRS 6 to 2, and flexion-extension motion becomes smooth.

This is not simple “muscle loosening.” It represents the reconstruction of the kinetic glide chain among the quadriceps, patella, fat pad, and synovial membrane — an integrated dynamic system that governs patellofemoral tracking and deep knee mechanics. The infrapatellar fat pad is not just a soft cushion; it is a biomechanical regulator of anterior knee motion. Recognizing its role fundamentally changes how we treat chronic anterior knee pain.

At RSM International Academy, both the Deep Tissue Massage Course and the Remedial Massage Program systematically teach this biomechanical understanding of the patellar fat pad through a combination of structural assessment, mobilization, and fascial release.

Students don’t simply memorize techniques — they learn to determine which layer, in what order, and in which direction to mobilize. This logical, evidence-based reasoning is the essence of Sports Medicine–based Manual Therapy that RSM promotes worldwide.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

References

1)Dye, S.F. (2005). The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: A tissue homeostasis perspective. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 436, 100–110.

2)Stecco, C., Gagey, O., Macchi, V., Porzionato, A., & De Caro, R. (2014). The infrapatellar fat pad and its role in knee biomechanics and pain. Journal of Anatomy, 224(2), 147–155.