RSM Blog: Manual Therapy Techniques

Neurophysiology of HVLA and LVLA – Mechanisms and Stepwise Approach

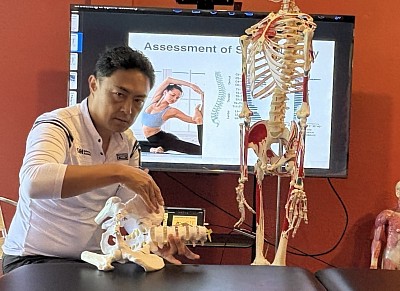

In the Orthopedic Massage for Spine Mobility and Breathing course at RSM International Academy,

HVLA (High-Velocity Low-Amplitude) and LVLA (Low-Velocity Low-Amplitude) joint manipulation are taught for pain reduction, postural improvement, functional recovery and sports performance with an emphasis on safety and neuromuscular re-education.

To optimise joint motion, the therapist first assesses misalignment caused by muscle tension, trigger points and fascial restriction, while palpating during massage and observing the kinetic chain through guided stretching to identify movement dysfunction.

HVLA is never performed abruptly. Treatment begins with superficial myofascial release and active soft-tissue release, followed by deep-layer soft-tissue release around the joint to reduce tension. Then, LVLA joint mobilisation restores physiological motion and promotes joint centralisation.

This sequence stimulates capsular mechanoreceptors (Types I & II), enhancing neural glide, joint position sense, and coordination. LVLA specifically facilitates postural control and sensory reintegration. RSM follows the principle “Release → LVLA → Minimal HVLA.”

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

RSM International Academy

References

1) Bialosky JE et al. (2009). Manual Therapy, 14(5), 531–538. [PubMed ID 19539559]

2) Pickar JG. (2002). Spine Journal, 2(5), 357–371. [PubMed ID 14589477]

Reed WR et al. (2020). Clinical Biomechanics, 73, 86–92. [PubMed ID 31958668]

3) Sterling M, Jull G. (2001). Manual Therapy, 6(3), 139–148. [PubMed ID 11414774]

Clinical Application of HVLA and LVLA – Safety and Evidence

At RSM International Academy, safety and patient specificity take priority in choosing between HVLA and LVLA.

For elderly or high-BMI clients with bone spurs, HVLA may detach micro-fragments and irritate nerves, so RSM uses a protocol centred on myofascial release, deep-tissue massage, and LVLA-dominant mobilisation.

HVLA is never performed on the cervical spine. Instead, alignment is corrected via deep-tissue methods, myofascial release, and towel-assisted LVLA traction for safe motion re-education.

In joint-manipulation sessions co-hosted with the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, professors shared clinical examples:

“When HVLA is applied to osteophytic segments, small bone fragments may migrate and compress nerves—hard to detect on MRI and very difficult to remove surgically.”

Based on these clinical findings, RSM strictly follows the stepwise protocol “Release → LVLA → Minimal HVLA.”

This approach naturally induces pain relief, range-of-motion recovery, and neuromuscular re-education,

enhancing post-surgical rehabilitation and athletic performance with minimal post-session soreness and sustained results.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

References

1) Puentedura EJ, Louw A. (2012). Physical Therapy, 92(7): 1097–1110. [PubMed ID 22654195]

2) Gorrell LM, Beffa R, Christensen MG. (2019). J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 42(1): 25–33. [PubMed ID 30509569]

3) Bialosky JE et al. (2018). J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 48(9): 656–664. [PubMed ID 30126184]

Manual Therapy Perspectives on ITBS: Fascial Adhesion, Glide Restriction, and Patellar Fat Pad Dysfunction

In many ITBS cases, pain originates not from the iliotibial band itself, but from adhesion and glide restriction between the Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL) and the superficial fascia of the lateral thigh. These adhesions create shearing tension along the fascial plane that connects to the vastus lateralis and the iliotibial tract, limiting smooth movement and producing lateral knee irritation.

The vastus lateralis often contains latent trigger points and myofascial densification, particularly around its junction with the iliotibial tract. This region is also where glide dysfunction occurs between the fascia of the lateral quadriceps and the IT band. Palpation typically reveals a rope-like thickening or tenderness beneath the superficial fascia.

Another common contributor is patellar fat pad fibrosis or alignment imbalance caused by quadriceps strength asymmetry — especially dominance of the rectus femoris over the vastus medialis. These imbalances shift patellar tracking laterally and increase ITB tension near Gerdy’s tubercle. In chronic cases, fascial adhesion around the fat pad and fibrosis of the deep retinaculum can be palpated.

At RSM International Academy, manual therapy for ITBS emphasizes:

- Releasing TFL and vastus lateralis adhesions through myofascial glide techniques

- Assessing trigger points and fascial fibrosis in the outer quadriceps

- Mobilizing the patellar fat pad to restore local tissue elasticity

- Evaluating Gerdy’s tubercle fascia and surrounding structures for restriction

- Re-educating muscular balance between rectus femoris and vastus medialis

This approach integrates palpation precision with kinetic-chain assessment to identify whether the dysfunction stems from fascial adhesion, patellar alignment, or proximal load transfer.

we learn to identify the true causes of ITBS-related pain through the Deep Tissue Massage Course and Remedial Massage courses. These skills not only relieve pain but also enhance performance and play a vital role in rehabilitation.

- Hironori Ikeda, MSc Sports Medicine

Manual Therapy & Neuro-Myofascial Release Specialist

References

1) Falvey ÉC, Clark RA, Franklyn-Miller A et al. The Iliotibial Band Syndrome: An Examination of the Evidence Behind a Number of Treatment Options. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(12):851-857.

2) Paoloni JA, Milne C, Orchard J. Manual Therapy and Soft Tissue Mobilization for Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Clinical Review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(8):588-595.